SPOKANE, Wash. — New information about private well testing out on the West Plains prompted a group of volunteers to ask for more testing in a much larger area.

Last month, the state of Washington started testing hundreds of private wells for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) contamination. That testing revealed more than half of the wells contain higher levels of PFAS than the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standard.

The news comes as the founder of the West Plains Water Coalition continues calling on the state and federal government to do more.

John Hancock has lived on the West Plains for 16 years, and he says it's everything he and his family have always dreamed of: good neighbors, stars, sunshine, wildlife and more.

But now, Hancock has contaminated drinking water.

In 2017, Fairchild Air Force Base announced the discovery of PFAS, sometimes referred to as "forever chemicals," in the public and private drinking water for thousands of residents in Airway Heights, Medical Lake and surrounding areas.

Now, seven years later, the contamination remains, and the city of Airway Heights is still buying clean drinking water from the city of Spokane, which comes from a different aquifer. For the thousands of homes using private wells, options are even more limited.

Several months ago, the Spokane International Airport (GEG) announced it, too, has contaminated groundwater from PFAS. It's the same problem in a new location, affecting even more property owners on even more private wells.

The aquifer that feeds the West Plains Region sits about 300 feet below the surface. The Grand Ronde Basalt is an underground formation more than 16 million years old, making up 65,000 square miles of groundwater.

About 300 feet below the surface, the Grand Ronde Basalt is constantly flowing. It's a formation more than 16 million years old, making up thousands of square miles of groundwater.

But what about the rest of the people in the West Plains who are outside of those contamination zones?

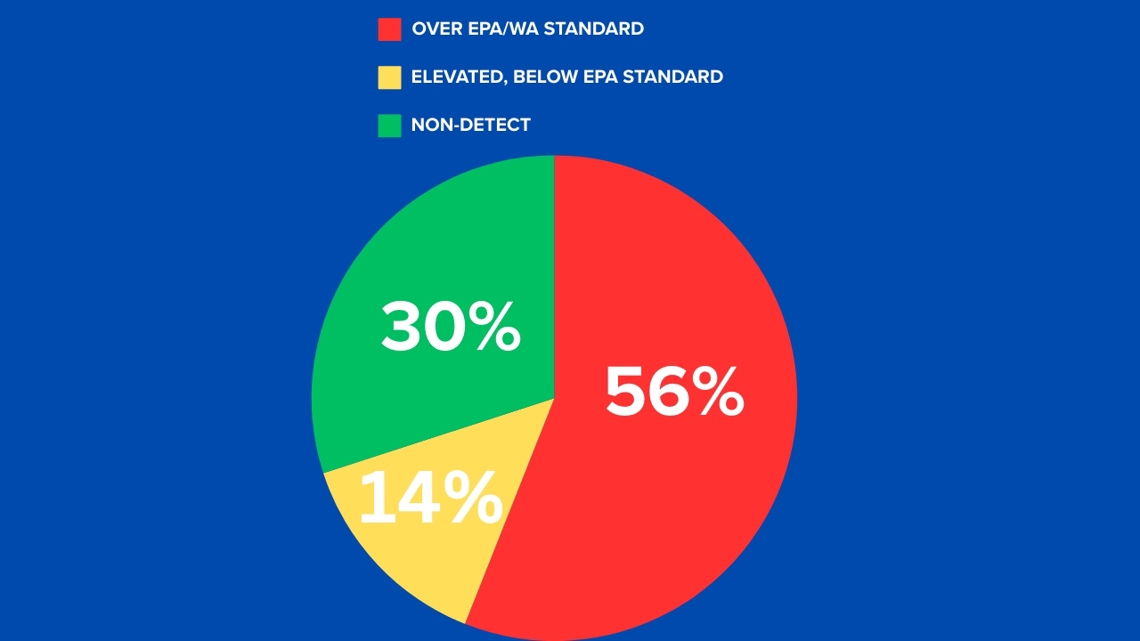

In March, the Washington State Department of Ecology (DOE) started free well testing for about 300 people in the "priority testing zone." An estimated 56% of the wells tested came back with readings higher than what the EPA considers safe. Another 14% came back elevated, but still below the EPA standard.

Only 30% came back as clean.

"The main or immediate goal is to get people drinking safe water," said Nicholas Acklam, a section manager with the DOE's Toxics Cleanup Program.

Those with contamination will start getting Culligan bottled water provided by the state. Then, the data is sent to Eastern Washington University (EWU), where a geology team is mapping contamination hot spots and projecting underground water flow.

"We're going to be creating heat maps, identifying where we're finding contamination," Acklam explained. "We'll be able to plug those results into the model that Eastern Washington is using, and we'll be able to determine if there are more areas of potential impact that we need to be looking at."

The process has been frustratingly slow, which is why Hancock and his coalition of more than 40 volunteers are pushing to get well testing paid for and available to anyone in the West Plains who worries their water could be contaminated. The effort got the attention of the feds at the EPA.

"EPA is saying it's not fair to the community that those people in the Fairchild zone get help and these people over here don't," Hancock said.

The coalition and DOE are also asking the Washington State Department of Health (DOH) for grant money to at least get basic filtration systems in the kitchens of homeowners who haven't been tested yet or don't yet qualify.

"You could look at the road and say, 'Well, the wells on this side are clean, and the wells on that side are not.' But that's a totally artificial boundary," Hancock said. "And we think it's just an arbitrary division because rocks and soil and water don't follow straight lines."

It's estimated there are more than 1,400 private wells on the West Plains could be contaminated.