Editor’s Note: Sometimes, it’s obvious.

The Pee Wee slugger ripping balls over the fence. The Pop Warner running back who pirouettes around defenders. The pint-sized point guard with the perfect crossover.

That was not Clayton Kershaw. Three decades ago, there was little sign of a chunky kid from Highland Park blossoming into perhaps the best athlete ever to come out of Dallas—and one of the greatest pitchers of all time. There was certainly no indication that he would come to embody so many things bigger than himself, arguably none larger than attaining and sustaining greatness in the face of sweeping change.

It’s a hell of a story, one I partly chronicled for D Magazine as the cover story of our April 2023 issue. But Kershaw’s journey and its ripples throughout baseball are so much wider than what can be conveyed in a single magazine piece.

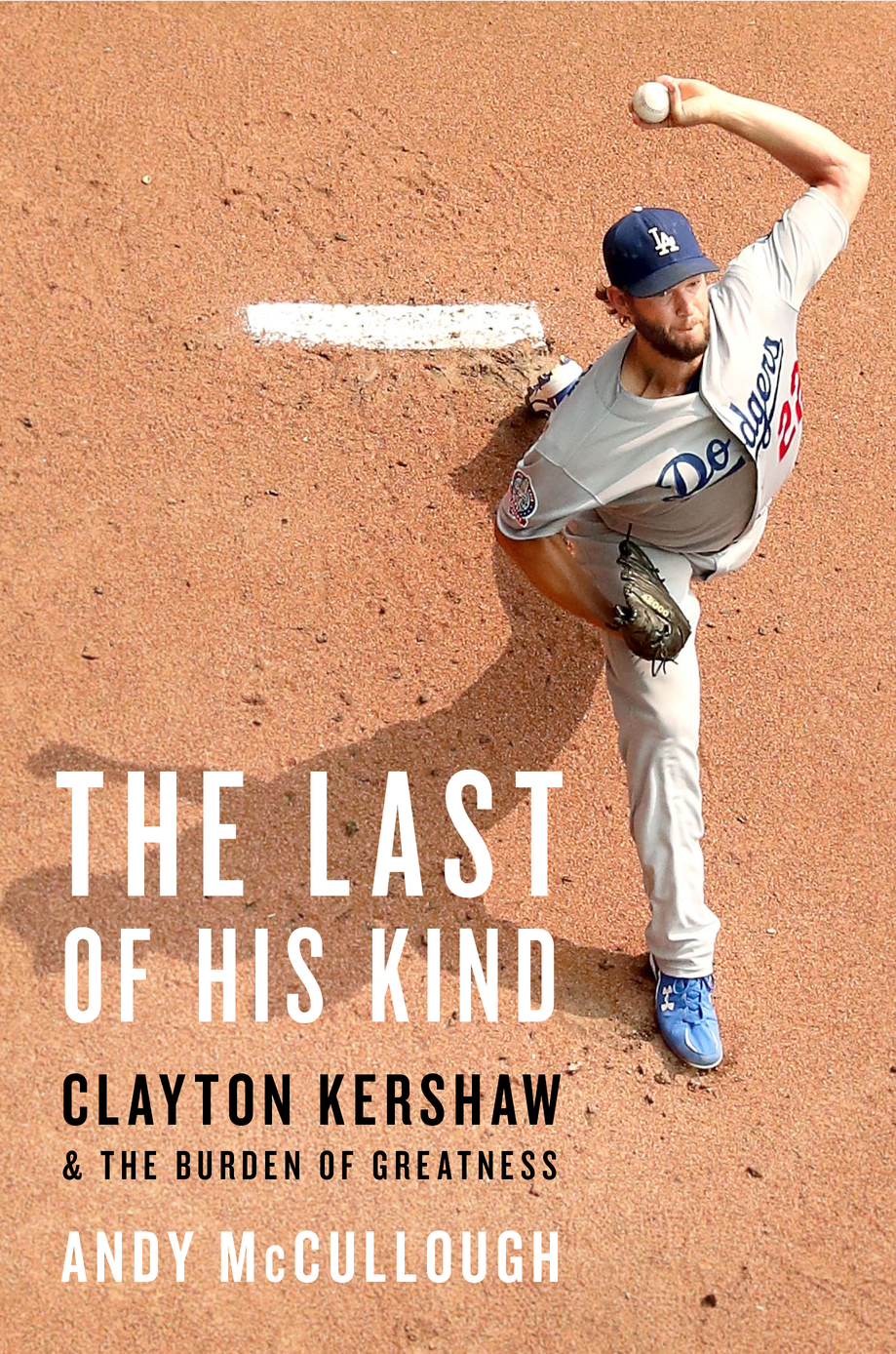

That’s where The Athletic’s Andy McCullough comes in. He’s been one of the best baseball writers in the country for more than a decade, a decent chunk of which he’s spent covering Kershaw and the Los Angeles Dodgers. It figured he’d eventually write a book and a damn good one at that, featuring more than 200 interviews and plenty of participation from Kershaw himself. It’s called The Last of His Kind: Clayton Kershaw and the Burden of Greatness, and it’s out now.

What follows is an excerpt from early 2006, just before Kershaw’s senior season with the Scots, when the baseball world was clued into how a pudgy lefty with some promise had transformed into a prodigy. All it took were hours of workouts at an Addison baseball complex, a mechanical overhaul by a guru named Skip, and a teenager with a fanatical desire to make it to the big leagues.

On a January afternoon in 2006, Seattle Mariners scout Mark Lummus answered his phone and scoffed at an invitation to witness history. On the other end of the line was Skip Johnson, a coach at Navarro College in Corsicana, Texas. Johnson asked Lummus to come to the D-Bat facility in Addison, more than an hour north of Lummus’s home in Cleburne. In the winter, Johnson moonlighted giving lessons. He was gaining a reputation as “a pitching whisperer,” Lummus recalled, and wanted to show off his latest pupil.

“Skip, no,” Lummus said. “I’ll see him when the season starts.”

Like plenty of scouts in the area, Lummus thought he knew about Clayton Kershaw. Good kid. Still pudgy. Decent fastball, big curveball. Not enough strikes. “He was a guy to keep tabs on,” Lummus recalled, not much more, as Kershaw approached his senior season at Highland Park High School. Lummus had played at the University of Texas with J. D. Smart, who was Kershaw’s advisor for the upcoming Major League Baseball draft. (To protect NCAA eligibility, agents were called “advisors.”) Smart had been in his ear, too. Lummus was skeptical. In his estimation, Kershaw needed to sharpen his game in college.

Lummus oversaw eleven states for the Mariners. His time was precious. But Johnson insisted. The two friends trusted each other. Lummus perked up when Johnson referenced Seattle’s place in the draft that June.

“Y’all pick in the top ten, right?” Johnson said. “Then you need to come see him.”

“To see Kershaw?” Lummus said.

“Mark,” Johnson said. “You need to come see this.”

✰✰✰

Arthur Ray Johnson was present at the creation of Clayton Kershaw’s greatness. He did not inspire it. He did not sustain it. He did not brew the cocktail of anxiety and restlessness and desire that elevated Kershaw above his peers in the class of 2006. But Johnson, known as “Skip” since boyhood, was the man who unlocked the door for Kershaw. He shaped the delivery that tormented generations of big league hitters.

They met before Kershaw’s senior season. The weight of responsibility hung on Kershaw’s shoulders. The draft was drawing closer. If he played well, he could net a signing bonus that could pay off the debts his mother, Marianne, incurred to afford to live in Highland Park. If he stumbled in his final year—or even worse, if he got hurt — his next step was less clear. Against that backdrop, Clayton and Marianne welcomed a procession of agents into their home. They hired Smart, a former big-league pitcher who worked with Hendricks Sports Management, the firm that represented Texas legends Roger Clemens and Andy Pettitte.

To Kershaw, part of Smart’s appeal was “he seemed like the most normal of the people.” Smart also understood Kershaw’s financial situation. When Kershaw met with a representative of the high powered baseball attorney Scott Boras, he was turned off by the suggestion that he attend college. The request was reasonable: most teams disliked offering sizable bonuses to high school pitchers. Boras had negotiated a $3.55 million deal for Wichita State pitcher Mike Pelfrey in 2005—the third-richest bonus in the draft, despite Pelfrey going ninth overall to the Mets. For amateur pitchers, many in the industry believed, the path to a life-changing bonus wended through college. Kershaw did not think he could wait. “His mom was so nervous that he was not going to get a scholarship,” recalled Ken Guthrie, who coached Kershaw’s travel ball team with D-Bat. Her son felt the same anxiety. He recognized he could not afford to live far from home. Stanford offered him a 90 percent scholarship, but for the Kershaws, 10 percent of life in Palo Alto was too pricey. His recruitment boiled down to Texas A&M and Oklahoma State. Each extended Kershaw a full ride, a relative rarity for college baseball. Kershaw opted to sign with A&M. He discussed rooming with his travel ball teammate, future big-league closer Zack Britton. A&M coach Rob Childress had an unexpected ally: Ellen Melson, Clayton’s girlfriend, came from a family of Aggies. Clayton committed to joining her—even if he wasn’t sure he would ever make it to campus. “Even with a full scholarship, I didn’t know how I was going to be able to go to college,” Kershaw recalled. “There’s stuff that costs money at college.”

Every spring, top high school prospects confer with their advisors to set a price for their services. Advisors used colleges as leverage: If you don’t hit this number, my client is headed to the SEC. But if you enrolled in a four-year school, you were not eligible to return to the draft for three seasons. So Kershaw asked Smart to bluff. He would accept any reasonable six-figure offer. If none came, Kershaw considered forgoing A&M for a junior college, where he could become eligible for the draft again in 2007.

As the season approached, Kershaw occupied a position unique to his ability and his geography. He was considered by college coaches, professional scouts, and accredited publications to be one of the better high school pitchers in the country. He was also the No. 3 starter for his travel ball team. D-Bat slotted a pair of pitchers ahead of him: Jordan Walden, a right-hander from Mansfield whose fastball touched 99 mph, and Shawn Tolleson, a close friend of Kershaw’s with an elite slider. Kershaw profiled as a second-tier prospect. “I never would have guessed he would do what he’s done,” recalled former Texas Rangers scout Randy Taylor. In December, Baseball America published a list of the top high school players. Walden ranked No. 1. Shawn Tolleson was No. 12. Kershaw landed at No. 32, in between a righthanded pitcher from Alabama named Cory Rasmus and a shortstop from Miami named Ryan Jackson. If he stayed healthy, he would be drafted. But there were dozens of kids ahead of him, plus an entire crop of college players. He was facing an uphill climb toward stabilizing his family’s finances. Around the time Baseball America printed that list, Smart rang Arthur Ray Johnson.

✰✰✰

“‘I’m not the best pitching coach,” Johnson insisted in January of 2023. “Don’t get me wrong. I’m not sitting here blowing smoke, like I’m somebody.”

Johnson spent years on the fringes. He grew up in Denton. He played for three small colleges in Texas. After earning a master’s degree in education, he took over the Navarro program in 1994. He offered lessons to any kid old enough to wear a glove. He insisted he was unsure of his prowess as a coach until a few years later, when he plugged into his VCR a tape of Brad Hawpe, a pitcher he had been tutoring.

Holy shit, Johnson told himself as he rewound the footage, look how much better he got.

Hawpe spent nearly a decade in the majors, but as a hitter. Johnson had a more profound effect on the boy he met at Smart’s request at D-Bat. Kershaw benefited from the wisdom Johnson had osmosed during his years coaching at every age level. Kershaw’s path to the Hall of Fame began, in a sense, with an exercise Johnson devised for children. It was called the 1-2-3 drill. “It’s probably the best drill to do for Little Leaguers,” Johnson recalled. For years, Kershaw had thrown with his left arm lowered about 50 degrees, known as a three-quarters arm angle. A lot of lefties threw like that. It deceived hitters. It also hurt his arm while limiting his velocity. Johnson wanted Kershaw to elevate his arm closer to his head and use his six-foot-four frame to his advantage. Johnson told Kershaw to act like his hands and his right leg were attached by a string. With every pitch, Kershaw gripped the baseball in his left hand, tucked inside the glove covering his right. When his hands rose, so should the leg: one. When his hands descended, the leg would follow: two. Only then, Johnson instructed, should Kershaw’s left hand leave the glove: three.

Kershaw practiced until his muscles absorbed the memory. Up. Down. Break. Up. Down. Break. One. Two. Three. His hands reached to the sky and his right knee ascended to his chest. When his knee straightened and lowered toward the ground, his hands followed suit and arrived at his chest. Only then did the two halves move in separate directions: he pulled the baseball from his glove with his left hand and swept it behind his left ear as his right leg stretched as far it could stretch toward the plate. The radar gun registered the difference: his fastball cracked the 90-mph barrier—and his arm didn’t hurt. “It felt more effortless,” he recalled. Kershaw repeated the movement in front of a mirror in his home. He practiced in the hallway at school. Up. Down. Break. Up. Down. Break. One. Two. Three.

The 1-2-3 drill mended another flaw. When scouts had watched Kershaw the summer before, he rushed to the plate, which sent fastballs flying out of control. The wildness reduced when he followed Johnson’s blueprint. His two halves moved in concert, sharpening his command and improving his velocity. It was a remarkable tweak. It also gave him a trademark. “Skip was the inventor of the gathering pause that he has,” Highland Park teammate Will Skelton recalled. To maintain his balance, at the end of the 1-2-3, Kershaw held himself in place, right foot in the air, momentarily frozen. In that instant, the baseball disappeared from the eyeline of hitters, only to emerge in a blur from behind his head.

In another drill, Johnson handed Kershaw a hockey puck. He told Kershaw to throw a curveball with it. Johnson emphasized two points: set in the back, throw it out front. The switch taught Kershaw “to throw with sick spin,” Johnson recalled. Rather than bend, the curveball began to snap. Imagine a clock: the ball started at twelve and plunged to six, movement that could not be generated from Kershaw’s old arm slot.

In Kershaw, Johnson found an eager pupil. But he did not find a wealthy one. After the first session, Kershaw pulled Johnson aside. “Skip,” Kershaw told him, “I can’t pay for a pitching lesson.” Johnson told Kershaw to pay what he could, when he could. Johnson stuck to his word. “His dad gave me twenty dollars one time,” Johnson recalled. “That was about it.” And so Johnson trekked about an hour north from Corsicana, twice a week, week after week, to sculpt Kershaw for free. “That’s what we do,” Johnson recalled. “That’s what we’re in coaching for.” Johnson met Kershaw about fifteen times that winter. The sessions were a revelation. “Man,” Kershaw recalled, “it just all came together.” He elevated his arm angle, which lessened the strain. He found balance on the mound, which created more strikes. And his velocity rose, which figured to impress scouts. “It was like we were shooting skeet in the building, he was throwing so hard,” Johnson recalled.

A month into the lessons, Johnson decided Kershaw was ready for an audition. He thought about Mark Lummus, who was helping Seattle decide about the fifth pick in the draft. Johnson gave his pal a call.

✰✰✰

When Lummus pulled into D-Bat that January evening, he discovered Johnson had also invited Yankees scout Mark Batchko. The audience was still small. Lummus walked past an indoor soccer game until he found Johnson, Kershaw, Batchko, and a catcher, with Marianne watching in the wings.

The first thing Lummus noticed was the sound. The fastball exploded into the catcher’s mitt, like a cannonade echoing off the walls. Up. Down. Break. Up. Down. Break. One. Two. Three. Lummus watched Kershaw pump strikes. “Do you want to throw some curveballs?” Johnson asked. Kershaw toed the rubber and unleashed one. Lummus listened as the pitch hissed through the air “like a buzzsaw.” It possessed the sort of violent beauty that made jaded lifers swoon.

“Do it again,” Johnson said.

Kershaw snapped off another.

And another.

And another.

Lummus noted the joy on Johnson’s face, the bashful thrill emanating from Kershaw, the smile from his mother. Lummus pulled Johnson aside, eager to share his excitement and loose command of art history. “This must have been what it was like to watch Da Vinci paint the Sistine Chapel,” Lummus said.

Lummus looked down at his own arm. The hairs were standing up.

✰✰✰

On the drive home, Lummus started making calls. He was enthralled with Kershaw—but he understood it would be hard to sell his superiors.

The Mariners had finished in last place in the American League West for two consecutive seasons. The team had not reached the postseason since 2001. Scouting director Bob Fontaine Jr. felt pressure from his boss, general manager Bill Bavasi, who felt pressure from his boss, CEO Howard Lincoln. Seattle “was trying to get back to winning ways as quickly as possible,” Fontaine recalled. The No. 5 pick could not be a teenager who needed several years of minor-league apprenticeship. Lummus knew this. But what he had seen, inside that facility in Addison, made him think Kershaw might not be a project.

“I honestly think,” Lummus told Mariners officials later that year, “that this guy has a chance to be as good as, if not the best, pitcher that’s ever come out of the state.”

✰✰✰

In early February, another scout arrived in Texas. He checked into the Marriott near the Dallas–Fort Worth airport. Logan White, the scouting director for the Los Angeles Dodgers, did not intend to stay long. He had come to watch two pitchers. He was considering selecting either of them with the seventh pick in the draft.

White climbed into a car with Calvin Jones, his eyes and ears on the ground in the area. The two men had played together in Seattle’s minor-league system. They spent a year riding buses through the Midwest and then another rumbling across California. White peaked in class-A baseball. Jones pitched two seasons in the majors. The Dodgers hired White to run the draft in 2001. A few years later, White hired Jones to scout Texas.

The first kid they saw was Jordan Walden, the right-handed stud from D-Bat. White wondered if he could stick as a starter. “Jordan Walden,” White recalled, “had a rough delivery.” High school hitters couldn’t handle it—but maybe Walden’s body couldn’t handle it, either. The risk felt significant.

A day later, White and Jones drove an hour east, toward Terrell, Texas. Highland Park was scrimmaging there. A collection of rival scouts crowded behind the plate. On the field, Kershaw was doing his rigorous stretching routine. White slinked to the bullpen to watch. Later in life, as he reflected on that first look, White wondered if he merely served as an instrument of God, as if divine forces used him to deliver Kershaw to the Dodgers. Because after only a handful of pitches, White experienced a sensation akin to what Lummus felt.

“It doesn’t happen very often,” White recalled, “where your whole being, your whole being, just tells you, ‘This guy is a dude. This guy is for real.’”

Kershaw threw only a handful of innings. He still lost the handle on the curveball. His delivery still looked stranger than the textbook recommendation. White could live with those imperfections. On the drive out of Terrell, the scouting director turned to his fellow former Wausau Timber.

“Man,” White told Jones, “we’ve got to stay on top of this guy.”

He wondered if he had seen the future of his franchise.

Excerpted from THE LAST OF HIS KIND: Clayton Kershaw and the Burden of Greatness. Available on May 7. Copyright @2024 by Andy McCullough and reprinted with permission from Hachette Books/Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.