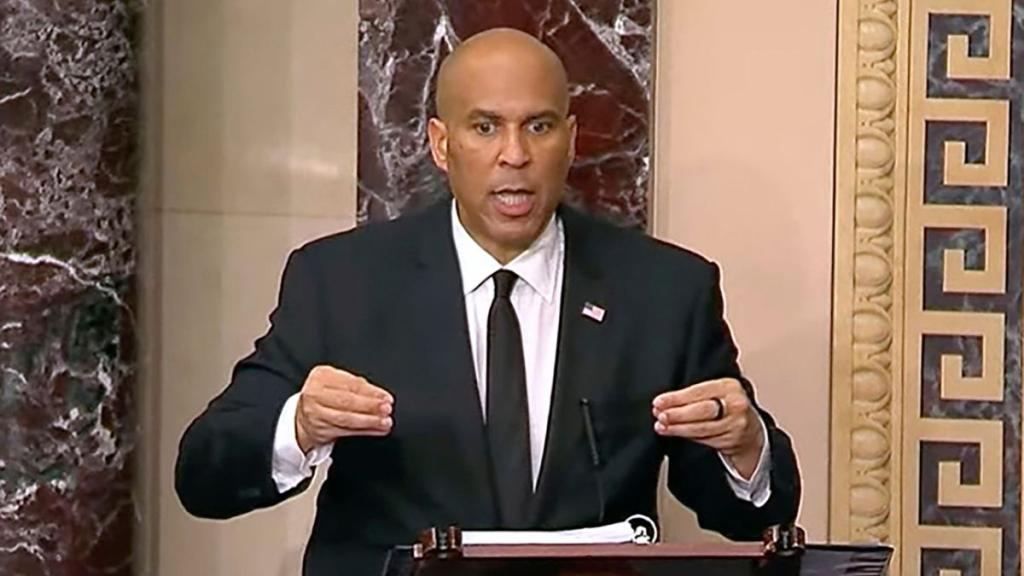

Preachers can learn important lessons from Senator Cory Booker and his speech that made history and brought moral clarity to a beleaguered nation.

From March 31st, 2025, at 7:00 p.m. to April 1st, 8:05 p.m., Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) spoke in protest of the Trump Administration, making the longest speech in Senate history. At 25 hours and 5 minutes, Booker broke the record of Sen. Strom Thurmond who filibustered for 24 hours and 18 minutes against the Civil Rights Act in 1957.

Booker’s historic speech disrupts “business as usual”

Booker’s speech took place during deliberations regarding the nomination of Matthew Whitaker as Trump’s ambassador to NATO. But the speech was directed at the voluminous illegal, immoral, and catastrophic policies and actions that Donald Trump and his advisor, Elon Musk, have made against the rule of law and the people of the United States.

“I rise tonight with the intention of disrupting the normal business of the United States Senate for as long as I am physically able,” he began. Booker proceeded to build a detailed and elaborate case against Trump’s and Musk’s violation of the Constitution. Pausing only to take questions from his fellow senators, he held the floor with a coherent, well-structured, moving, and powerful speech about what it means to uphold the ideals of America.

Why is Sen. Booker’s speech a learning moment for preachers?

I’ve been an ordained minister since 2000 and a professor of preaching and worship for the past nine years. I also co-wrote a textbook on the basics of preaching. So when I listen to sermons, I think about how a preacher crafts their message. I listen for the claims they make and how they apply those claims in their particular context. I work with students to articulate their intended purpose for the sermon. Also, I note their use of rhetorical devices, the sermon’s structure, and how they use their voice and body in their preaching.

In fact, I bring my homiletical eyes and ears to nearly every speech event I watch and listen to. While I did not see the entire 25-hour span of Cory Booker’s speech, I did watch several hours of it. And I thought about what I was witnessing from the perspective of a preacher and teacher of preaching.

At first, it may seem that Booker’s Senate speech has little in common with a preacher’s sermon in a Sunday morning worship service. Granted, no preacher should stand at the pulpit for 25 hours without food or a bathroom break, or even without a chance to rest in a chair.

But aside from the marathon aspect of Booker’s speech, there are significant lessons that preachers can learn from this historic event.

8 Lessons for Preachers from Cory Booker’s Historic Senate Speech

1 – Use the words of your community’s sacred texts.

Booker drew on historical documents, letters from his constituents, and even the Bible to make his appeal for the country to fight the descent into moral deterioration and fascism. With unflagging energy, enthusiasm, and determination, he offered an alternative vision for the nation based on ethical ideals and bipartisan cooperation.

He implored the American people to live into the founding ideal of this country first articulated in the U.S. Constitution: “We the people.”

“Let’s get back to the ideals that others are threatening, let’s get back to our founding documents,” he said. Booker reminded listeners of the final words in the Declaration of Independence, “we must mutually pledge, pledge to each other ‘our lives, our fortunes, and our Sacred Honor.’”

He also pitched to Delaware senator Chris Coons, a Yale Divinity School graduate, who quoted from the prophet Isaiah and talked about the Bible’s attitude toward the poor. Further, Booker implicitly invoked a biblical teaching about God’s word being “written on our hearts” (Psalm 37:31, Proverbs 7:3, Jeremiah 31:33, 2 Corinthians 3:2-3, Hebrews 8:10) when he asked, “Where does the Constitution live, on paper or in our hearts?”

What can preachers learn from this?

In an era of Christian nationalism where some leaders misquote, misinterpret, or misuse Scripture to attack the vulnerable and provide religious justification for authoritarianism, it is vital for preachers to convey the Bible’s message of justice and ethical righteousness.

When those in power twist or simply ignore the teachings of Jesus or use Christianity as a tool for culture wars and political grievances, Christians are obligated to speak out, stand up, and hold the line against capitulating to christofascism.

It’s up to preachers to provide sound principles based on critical engagement with the Bible to guide parishioners as they think about how faith can inform and shape the relationship between the church and public policy. In other words, it’s not a matter of whether the church and Christians should be involved in shaping laws and policy, but why and to what purpose.

I encourage preachers to have the courage demonstrated by Cory Booker to say what they mean, speak from the heart, and do it with integrity based on what the Bible and our theological convictions call us to believe and act on.

2 – Prepare, prepare, prepare.

While Cory Booker was the one at the stand for 25 hours, he did not create the speech on his own. His staff compiled multiple three-ring binders of the historical research they conducted and information they collected about the atrocities committed by the Trump administration. They also curated powerful stories about the heartbreaking and deleterious effects Trump’s and Musk’s actions have had on real people over the last 72 days since Trump came to power. This kind of crowd-sourcing gave authenticity, depth, and breadth to Booker’s historic speech.

He also prepared himself mentally and physically for the marathon. He keeps himself physically fit and, for this marathon, fasted so that he would not need to use the restroom. Also, he did not strain his voice so that he could sustain the speech over the 25-hour period.

What can preachers learn from this?

Obviously, preachers should not deprive themselves of food, drink, or sleep in order to deliver their weekly sermons. But it’s the discipline that Booker exemplified that preachers can emulate. Keeping up a regular practice of study, prayer and meditation, exercise, and healthy eating and sleeping are essential to “protect the asset” of the preacher’s voice and body.

In terms of content preparation, preachers can draw on crowdsourcing to help develop their sermons, just as Booker did with his speech. Talk with parishioners about the text for your sermon to get their perspective. Meet with other clergy who are working on sermons to share exegetical insights and ideas for approaching the text.

Also, use your social media platforms to pose a question you’ll be addressing in your sermon and ask for people’s thoughts. Or post a word, phrase, or image that is related to your sermon and ask people to share their impressions, questions, and stories. While you won’t be able to use all of it in the sermon, it’s likely that this kind of crowdsourcing will provide you with imagery, stories, and questions that can help frame and give texture to your sermon, just as Booker did in his speech.

3 – Use your moral authority as well as your relational influence.

In addition to detailing the ways in which the Trump regime is destroying American democracy, Booker’s speech castigated his Senate colleagues for failing to fulfill their Constitutional obligation to serve as a co-equal branch of the U.S. government. He called out their failure to hold hearings investigating things such as the illegal firings of government workers, kidnapping and deporting people who have committed no crimes, and carrying out military operations using unsecure communication channels. He lambasted his congressional colleagues for allowing Trump and Musk to run roughshod over the Constitution as well as the norms and laws of the country.

More importantly, Booker called on the American people to claim their power and unite across party lines to protect each other and their communities from Trump and Musk’s onslaught. “In this democracy,” he said, “the power of the people is greater than the people in power.”

What can preachers learn from this?

In my book, Preaching and Social Issues, I argue that “the needs of the most vulnerable in our society, as well as the breakdown of civic engagement, call for a renewed vision of our highest moral and ethical aspirations. Preachers can name the qualities and principles that should guide a congregation’s discernment around social issues and remind listeners that things like inclusivity, compassion, and helping those in need are integral to the very nature of the God whom Christians worship.”

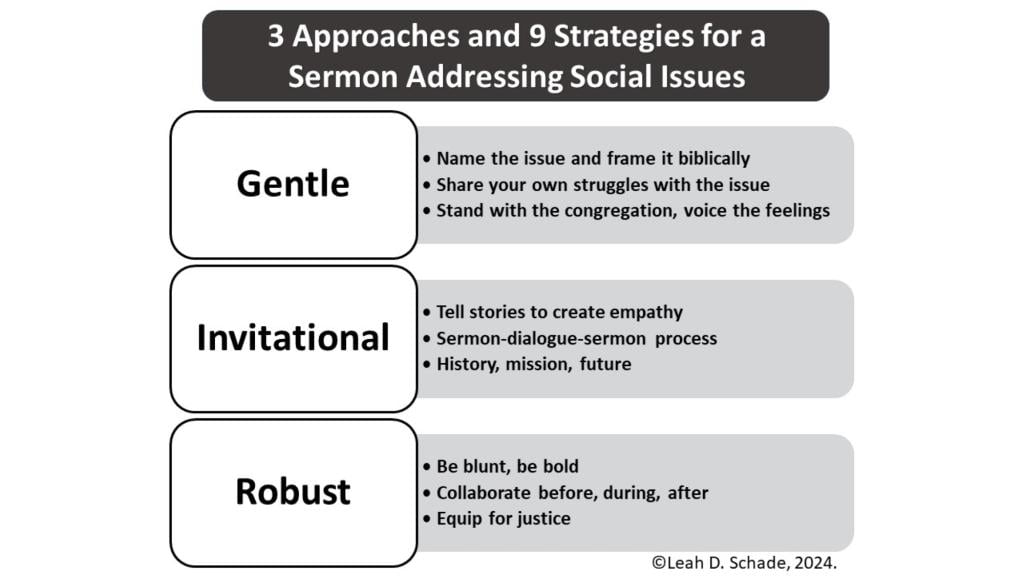

This is not to say that such a task is easy or without risk. In fact, I developed an assessment tool to help pastors gauge the risks and strengths of their social location, their congregation, and the relationships therein to discern what approaches to take for exercising their moral authority and relational influence.

But whatever your path is for prophetic preaching, embracing your moral authority and ethical integrity, as Booker did, is paramount. It requires the courage to speak genuinely from the heart and to align your words with ethical foundations, theological convictions, and the teachings of the Bible.

4 – Use a through-line.

Throughout his speech, Booker reminded his listeners that “This is our moral moment.” He emphasized that because these are not normal times, “it’s not about right versus left, but about right versus wrong,” a phrase he reiterated multiple times. He also repeatedly called on Americans to “redeem the dream.”

Repetition of a phrase is called using a “through-line.” It not only builds cohesion by creating moments of recognition and resonance, it can also be used to build dramatic tension. For example, in order to take questions without giving up his time, Booker had to recite this precise verbal formula: “I yield for a question while retaining the floor.” This became a catch phrase that will likely make its way into memes and popular culture for years to come.

What can preachers learn from this?

In her book, Novel Preaching: Tips from Top Writers for Crafting Creative Sermons, Alyce McKenzie notes that the through-line is a technique used by fiction writers and screenwriters. A repeating idea, image, or phrase can also give coherence to a sermon as well as build dramatic tension. This allows the listeners to track with the preacher, tune back in if they got distracted, and carry a key phrase with them after the sermon concludes.

Cory Booker used throughlines very effectively in his marathon speech, and preachers can do the same in their sermons.

5 – Use a bookend.

Cory Booker began by dedicating his speech to Rep. John Lewis, a civil rights activist who inspired Booker and mentored him on the sacred duty of standing up for what is right as an elected official. He invoked Lewis’s famous admonition to “get in good trouble, necessary trouble. Help redeem the soul of America.”

Booker said that he was holding himself to that standard. He explained that he felt called to respond to the crisis in this country “because so many of the people that have been reaching out to my office in pain, in fear, having their lives upended” – regardless of their party affiliation.

25 hours later, he concluded his speech by coming back to Rep. Lewis. “It is time to heed the words of the man I began this whole thing with: John Lewis . . . He said he had to do something. He would not normalize a moment like this, would not just go along with business as usual. . . [Lewis] said for us to go out and cause some good trouble, necessary trouble, to redeem the soul of our nation.”

The technique Booker used to begin and end his speech is called a “bookend,” which is where the speech starts and finishes with the same idea, phrase, image, verse of a song, or some pointed detail.

What can preachers learn from this?

Preachers can use the bookend to great effect in their sermons. For example, a sermon might introduce a story at the beginning, then mention it at the end to reinforce the point of the message. Or the preacher could introduce a metaphor for understanding God at the start of the sermon and circle back to it at the end – either to reaffirm or contradict it. The preacher could also describe a character at the sermon’s beginning and come back to that person at the end to draw out implications of the message, which is what Booker did in his speech.

Bookends can be very satisfying for the listener for several reasons:

- There is a feeling of resolution and closure when the end of the sermon recapitulates what the listener heard at the beginning.

- A bookend can reinforce the central claim by reiterating a theological point made at the beginning.

- A bookend can provide an “Aha” moment at the end of the sermon if the preacher references something they said at the beginning and shifts it slightly at the end to give it new or enhanced meaning.

Cory Booker used the bookend in his speech, and preachers can use this same rhetorical device to both begin and end their sermons.

6 – Use appropriate drama and performance techniques.

Unlike many of his predecessors who filled their filibusters by reading from the encyclopedia or slogging through with dry, boring prose, Booker was engaging, personable, and even entertaining at times. While some may decry his approach as too “theatrical,” the reality is that politics requires a certain type of performance to make its appeal.

Steven Zeitchik of The Hollywood Reporter noted the facility with which Booker used techniques from popular entertainment. “What Booker was doing was nothing less than creating a cinematic spectacle, a binge-worthy awards contender in which all 25 hours happened to drop at once,” he said. “Focus on different throughlines of Booker’s performance and you’d experience different arcs; come in at different moment and you’d infer different genres.”

We can also note Booker’s use of humor and comedy, such as pointing out the ridiculousness of Musk’s take on Social Security, and good-natured teasing of his colleagues in the Senate in order to build rapport.

What can preachers learn from this?

In A Sermon Workbook: Exercises in the Art and Craft of Preaching, Thomas Troeger and Leonora Tubbs Tisdale explain, “We need always to remember that a congregation sees and hears rather than reads a sermon. . . Preachers do not just create sermons. They perform sermons” (71).

Is a sermon really a performance? This term may be off-putting to some given that the word perform is usually associated with entertainment. But in her book, I Refuse to Preach a Boring Sermon, Karyn Wiseman says, “Preaching needs creativity and imagination almost more than anything else to avoid the chance of being boring or uninspiring” (47).

Wiseman acknowledges that preaching a sermon certainly requires “deliberate exegesis, contextual study, personal prayer, meticulous preparation, careful analysis, presentation practice, and other necessary elements.” However, she also notes that “for preaching to ignite the fires in the belly of those hearing the sermon there often needs to be something to catch their imagination, to spark their creative thoughts, and to push their minds to see where the word, the sermon, and the preacher are going.”

As Booker modelled in his speech, this type of creativity invites people to engage with the message in innovative and fresh ways.

7 – Be authentic and convey a sense of presence.

One of the most endearing aspects of Cory Booker’s speech was the way he owned what he was doing and acknowledged the challenge he had undertaken. He joked about the length of time he was speaking. He poked fun at himself for loving to be in the spotlight and having the mic.

Booker also made personal, heartfelt remarks about his Senate colleagues who gave him breaks with their questions. And he thanked his staff who helped him prepare so well for the speech with substantive facts and historical details. All of this put his listeners on his side and conveyed his authenticity and presence in the moment.

What can preachers learn from this?

Most people long for leaders who are honest, have integrity, and demonstrate congruence between what they say and how they act. Preachers attain this congruence when their theological commitments are in alignment with their embodiment in preaching. The result is authenticity and a sense of presence.

Authenticity, according to John McClure, is a matter of “ensuring that words and emotions match in such a way that the preacher is actually living inside the words that he or she is speaking,” (Preaching Words: 144 Key Terms in Homiletics [Westminster John Knox Press, 2007], 6).

Genuine humility, appropriate self-deprecating humor, being attentive, open, centered, and poised in preaching all contribute to authenticity and presence.

As Ron Allen reminds us, “The preacher needs to signal that he or she is attentive to the congregation and is emotionally, intellectually, and physically open to the community. There is no inventory of characteristics to determine presence, but the congregation draws more deeply into the sermon when they sense it.” (Preaching: An Essential Guide [Abingdon Press, 2002], 108).

The growing number of viewers over the 25-hour event attests to Booker drawing people into his speech. Likewise, when a preacher is authentic in the pulpit, this allows them to be fully present to their own selves, to God’s word, and to the congregation. In other words, communicating clearly about who God is and what God does – and what this means for the community – is conveyed through our speech and exemplified in our bodies as we are present with our listeners and the preaching moment.

8 – Use multiple platforms to convey your message.

Cory Booker has been at the forefront of using emerging social media platforms to reach his constituents, and the same was true for this event. Not only was the speech viewed by millions on the livestreams of C-SPAN and YouTube, but it also had 350 million likes on TikTok, a platform primarily used by youth and young adults.

What can preachers learn from this?

The more ways that preachers can share their message, the more people will engage. This means expanding beyond the pulpit and even the church’s Facebook or YouTube feed. Share clips from your sermon on platforms like Instagram, Threads, BlueSky, and TikTok. This will enable you to reach more people with messages that can counter the hate-filled, bigoted, and theologically harmful messages of right-wing Christian media.

If technology and social media are not your forte, find someone in your church or in your community who can help. Ask your youth to help you create snippets of the sermon to share on these platforms. Make them digestible morsels that will capture people’s attention, give them a bite of ethical truth and spiritual nourishment, and keep them coming back for more.

Facing down the Goliath of oligarchical, christofascist White supremacy

As Cory Booker approached Thurmond’s record in the 23rd hour, the viewership grew to 300,000 at its peak. Questions of “Will he make it?” turned into cheers of celebration when he defeated the record of the man who tried to thwart equal rights in America nearly seven decades ago.

However, Strom Thurmond’s ghost still haunts us today. In fact, it has possessed the White supremacist oligarchy that has currently overtaken this country. Thurmond may have lost his bigoted battle in 1957. But the war for the soul of America raged on, and at this moment, Thurmond’s successors are surpassing his wildest racist dreams.

That’s what Cory Booker, like David with a handful of stones (1 Samuel 17), faced down in his speech against the Goliaths of Trump, Musk, and the christofascist oligarchy.

But it will take more than a single stone to topple the behemoth in front of us. Each of us must grab our slingshots and our bag of smooth stones (1 Sam. 17:40) as we enter the fray to defend the vulnerable, reinstate the rule of law, and restore the highest ideals of this country.

Being part of something that matters

Preachers have a key role to play in this work. They can draw on their theological and biblical training, their pastoral care skills, their know-how in community organizing, and their moral and ethical authority to inspire people to follow through on what Booker started.

As Zeitchik said, Booker gave us “the sense that we are part of something that matters.” That is a core task for every preacher. And even more, to inspire them to “finish the story.” Or, at least, to bend the arc of that story away from moral collapse and toward moral renewal.

Read also:

11 Lessons for Preachers from Bishop Budde’s Sermon

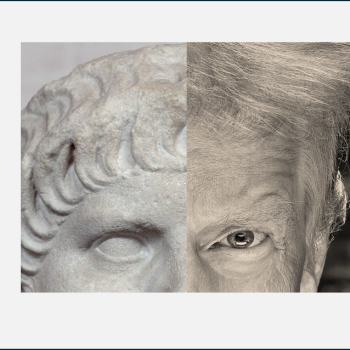

5 Tips for Clergy to Survive the Riptide of Trump 2.0

- Are you a preacher in the U.S.? You can help me with my research studying ministry, preaching, and social issues during this unprecedented time by filling out this 15-minute survey.

- Thinking of addressing social issues in a sermon? Preachers can take this 5-minute assessment of their strengths and vulnerabilities here.

- Are you a clergy person looking to connect with other Christian leaders in the work of resisting and disrupting Christian nationalism? Check out the Clergy Emergency League, a group I co-founded in 2020.

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Associate Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching and Social Issues: Tools and Tactics for Empowering Your Prophetic Voice (Rowman & Littlefield, 2024), Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Her book, Introduction to Preaching: Scripture, Theology, and Sermon Preparation, was co-authored with Jerry L. Sumney and Emily Askew (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023).

BlueSky: https://bsky.app/profile/leahschade.bsky.social

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/