Go with the Flō : Jonathan Jaglom’s journey from Swiss prince to Israeli patriot

Jonathan Jaglom grew up in Geneva with immense wealth, living in the heavy shadow of his domineering grandmother, who raised millions for WIZO, and his father, who made hundreds of millions from his investment in the 3D printer company Objet. After his first round of fundraising for his own startup, Flō Optics, Jaglom broke a long-standing tradition of silence in one of Israel’s wealthiest yet most secretive families.

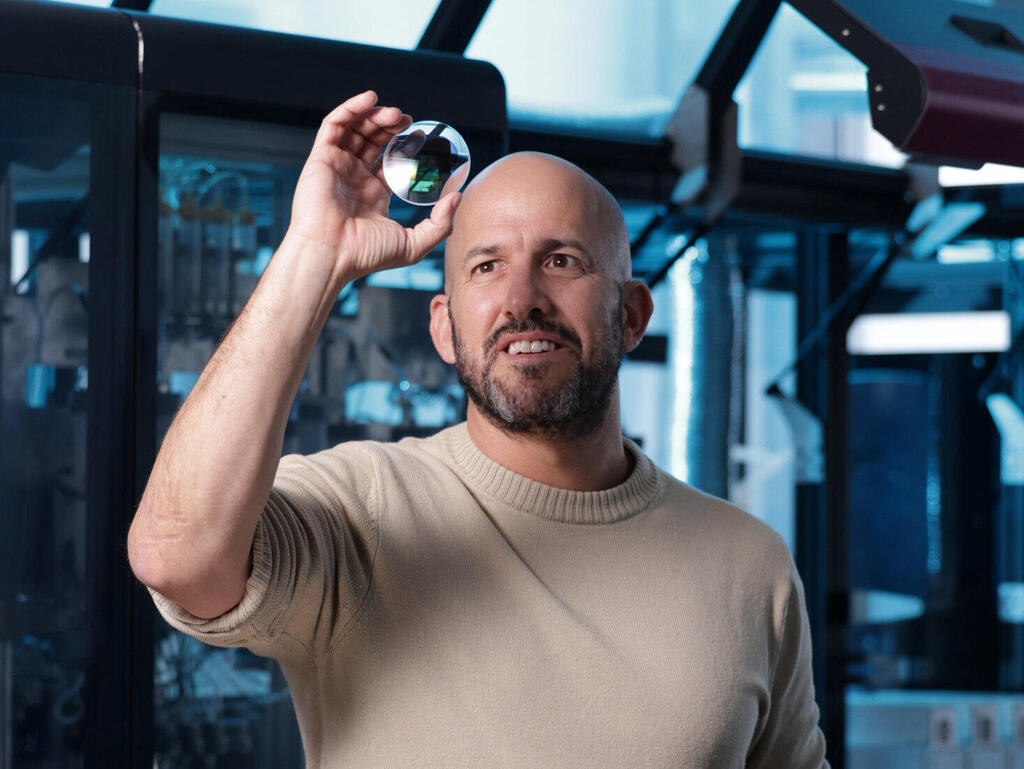

If his startup weren’t in the printing industry—long associated with his family’s considerable wealth—it’s likely that entrepreneur Jonathan Jaglom would have continued the family tradition of staying out of the spotlight and avoiding interviews. But Jaglom (48), the grandson of Raya and Joseph Jaglom and son of veteran investor Elan Jaglom, who made hundreds of millions of dollars from his investment in 3D printer manufacturer Objet, is operating squarely within the family business. Flō Optics, the company he founded in 2019 and which recently completed a $35 million funding round, aims to revolutionize the way eyeglass lenses are printed. If the investment pays off and the machine the company is developing delivers on its promise, Jaglom hopes to use it to write a new and significant chapter in the family’s printing legacy—this time, on his own terms.

Jaglom represents the third generation of one of Israel’s wealthiest yet most secretive families. Aside from publicly lending part of its art collection to the Tel Aviv Museum, the Jaglom family has long avoided the public eye. Jonathan was born in Geneva, where his grandfather Joseph made finance the center of his life, running the family’s investment fund alongside his son, Elan.

In the 1990s, Elan began investing in Israeli tech companies. His 1998 bet on Objet, then a promising startup developing 3D printers, proved highly successful and helped cement the family’s identity in the tech world. In 2012, Objet merged with its leading American rival, Stratasys, creating one of the dominant companies in 3D printing—at a time when the field appeared to hold the key to the future.

As the first and largest investor in Objet, Elan Jaglom sold his shares in the merged company shortly thereafter, when its valuation had soared to around $6.5 billion. His personal gain is estimated at $360 million. In 2013, after the sale, Objet's founders and early investors sued Jaglom, alleging that their stakes had been unfairly diluted, costing them hundreds of millions of dollars. The dispute was settled out of court in 2017. In the years that followed, the waning hype around the sector caused Stratasys’s value to plummet. The company now trades at a valuation of just $700 million.

Jonathan Jaglom joined Objet in 2005, at age 29. He began as sales manager for Eastern Europe, moved on to become European marketing manager, and later VP of sales and operations. He was eventually promoted to head of the Asia-Pacific region, and in 2015, was appointed CEO of MakerBot, a company Stratasys had acquired.

“I came to Objet after a stint in real estate entrepreneurship in Cyprus, where I didn’t find my footing,” he says in an interview with Calcalist. “It was a dark period for me. Then Danny (his brother) and Elan (he refers to his father by first name since they began working together) suggested I join Objet, and I said, ‘Let’s go.’ Elan laid out tough entry conditions—very Soviet-style: performance-based goals, no leniency if I failed, and a starting salary equal to that of a secretary.”

Why did Stratasys ultimately falter?

“You can’t call a company with a billion dollars in sales a failure, but its declining value shows something went wrong. It lost focus and tried to appeal to too many markets.”

You were one of the five senior executives at Stratasys. What did you do about it?

“I raised concerns, but with so many shareholders, it was nearly impossible to push forward meaningful changes.”

In 2017, after 12 years with Objet-Stratasys, Jaglom left to build something of his own. “I spent three years looking for my next move, and now I’m applying the lessons I learned at Flō Optics,” he says.

It sounds like Flō is your response to the Stratasys experience.

“Elan had a good company. He sold after the merger—he doesn’t need a fix. Stratasys is Elan’s story. Flō is mine. I’ve learned a lot from Stratasys, and I’m trying not to repeat the same mistakes. But I’m not doing this to please my father. I’m driven by the desire to succeed in this printing dynasty. There’s a legacy here I don’t want to mess up. For Elan, Flō is the continuation of what Stratasys could have been—the positive continuation of that story.”

The Jaglom family is often described as Israeli “nobility”—with financial strength, ties to Israel’s founding elite, connections with global Jewish communities, and the old-world European style once common in Tel Aviv’s upper class. The family’s wealth was built by Jonathan’s grandfather Joseph and his three brothers, who amassed a fortune in Switzerland through real estate, factory deals, and other investments.

His grandmother, Raya, came from another prominent lineage. Her father operated a chain of banks in Bessarabia (modern-day Moldova and Romania), but unlike her husband, her life centered in Israel. After immigrating to Mandatory Palestine in 1939, she joined WIZO (Women’s International Zionist Organization), and over decades connected Jewish leaders and philanthropists across the world with Israeli causes. From 1970 to 1996, she served as President of World WIZO, raising funds and founding Jewish federations globally. She passed away eight years ago at the age of 98.

“Grandma was a powerhouse who had a huge influence on me,” says Jonathan. “I think about Elan growing up with such a strong mother—it couldn’t have been easy. If your mom was like my grandmother when you were a kid… good luck. Zionism in our family started with her. People say Begin or Eshkol offered her a ministerial post, but she refused. Her role was fundraising for WIZO. They say that one donor, Francis Minkoff, would answer her call with: ‘Raya, how much?’ She’d say ‘Seven million,’ and he’d say ‘Okay.’ A 10-second call. She always got what she wanted. Everyone knew that if Raya Jaglom called, it was about money.”

What was her relationship with your grandfather like?

“It was kind of a funny mismatch. She was the dominant one, the bulldozer. He was soft, beloved, and never got angry. When they walked into a room, you knew exactly who to look at. Visiting Grandma felt like visiting royalty. She lived in a beautiful penthouse near Kikar Hamedina in Tel Aviv, and everything—furniture, art, dining sets—was impeccable. On Passover, the staff would clear the table. We knew: at Grandma’s, we were with the royal family. Three days before she died, she was still going to the hairdresser. Two days before, she told me, ‘I don’t understand. I’m taking all the medicine they give me. Why can’t they fix me?’”

And what was she like outside the family?

“When I was 12, I saw her speak at a UN event in Geneva. There were maybe a thousand people in the hall. As she began, the crowd kept chatting. She stopped and said, ‘This won’t work. Either you speak or I speak—but not both.’ She silenced the room, thanked them, and continued.

“Another time at the Weizmann Institute, they laid a cornerstone in memory of a family member. My dad was invited to speak. Grandma and Mom were sitting next to me. Dad got emotional and choked up. From her seat, Grandma barked, ‘Speak louder—we can’t hear you.’ Mom whispered, ‘Can’t you see he’s emotional?’ Grandma shot back, ‘That’s exactly why!’ That was her way of snapping him out of it. She had that power. You didn’t mess with Raya Jaglom.”

Jaglom's parents, Nurit and Elan, live in Switzerland, but over the years they have split their time between Geneva and Tel Aviv. Today, his sister Dafna lives in Switzerland, while he and his older brother Daniel — the owner of a hedge fund — live in Israel.

When Jaglom talks about the first meeting between his mother — the daughter of a socialist family from Tiberias who was working as a flight attendant at the time — and his domineering grandmother, it’s hard not to think of scenes from the Israeli comedy film Charlie and a Half.

"Grandma invited the 'Tiberian' to tea at the golf club in Caesarea," he says. "It wasn’t easy to be accepted into the family when you didn’t come from the Rothschild or Recanati families, but eventually Mom earned her place and gained respect as a wife. And while Dad was constantly busy, it was Mom who raised us, instilled Zionist values, sent us to Israel every summer for vacations, and made sure we enlisted in the IDF. Danny was a fighter pilot, I served in the Moran unit, and Dafna was in the Air Force."

What was it like growing up in Geneva?

"On the one hand, we received an outstanding education at an international school with the children of diplomats. I was on the Swiss youth rugby team, and in the winters we went skiing. We spoke Hebrew at home, French in the neighborhood, and English at school. But on the other hand, life in Geneva is quite depressing. You come home from school in the dark. It's a Calvinist city, with a culture of puritanical modesty. Not like Beverly Hills, where everything is flashy. Don’t get me wrong — there are a lot of wealthy people there — but wealth in Israel is far more visible."

But beneath the surface of Swiss civility and openness, deep currents of anti-Semitism occasionally surfaced. One such incident left a lasting mark on young Jaglom and later influenced his decision to immigrate to Israel.

"I remember when I was 13, we went on vacation to a cabin we had in the mountains," he says. "As we got out of the car, I heard my mother tell Elan, 'Put the kids back in the car,' and then I saw her come out with a sponge and a bucket to scrub off a Star of David someone had sprayed on our house."

What did that experience do to you?

"In a country where things like that happen, it’s impossible to feel truly at home. My sense of identity has always been personal, so the day after my last high school exam, I left Switzerland. I didn’t even stay for the graduation party. I wanted to put an end to it. I knew I was Israeli, and I knew I wanted to be a fighter and an officer. I had known that since I was eight."

After growing up like a Swiss prince — with wealth, summer homes, and plenty of pampering — how did you adjust to Israeli life?

"It happened in the army, and I vividly remember how naïve I was. At the induction center, when they asked, 'Who speaks French?' I raised my hand, and the sergeant immediately said, 'Great, go clean the toilets,'" he laughs. "The army taught me a lot. In survival situations, you quickly realize there’s no room for Swiss manners — you have to communicate directly and effectively.

"I got my first punishment in the IDF because I said 'sorry' too many times. The commanders warned me that if I said it again, I’d have to start running — and that’s exactly what happened. On the other hand, when my grandma sent Swiss chocolates, the whole tent went crazy over them.

"My brother wrote to me at the time, ‘The transition from Swiss prince to Israeli soldier isn’t easy.’ But despite that, I did well in the army and grew up a lot. I even served in the reserves for 15 years. No one can take that away from me. I’m not privileged — I’m a Zionist."

Still, when asked whether he might one day leave Israel, Jaglom doesn’t rule it out.

"That’s the beauty of living in a global world. We lived in Hong Kong for three years, in New York for almost three years, and before that in Switzerland. A few hundred years ago, your world began and ended in the village you were born in — maybe you’d go as far as your horse and cart could take you. Life is short, and you want to make the most of it. There’s nothing wrong with that. But I’m optimistic about life here."

So how do you see yourself today — more Swiss or more Israeli?

"I have both sides."

The tension between growing up in a wealthy family and the need to prove himself comes up more than once in conversation. One story he shares highlights this contrast clearly.

"At 18, I got a car — a green 1989 Golf that cost 800 Swiss francs," he recalls. "The only time in my life I came close to dying was because of that car. Its engine failed on the highway, and I nearly got hit by a truck. That evening, when Dad came home, I was furious. I threw him the keys and said, 'You and your idea of education almost killed your son.'"

How would you define that education?

"Be humble, work hard, and prove yourself — to yourself."

Did this attitude show up in other ways?

"Yes. For example, every summer, the entire extended Jaglom family would stay for two or three weeks at the Palace Hotel — one of the most luxurious in Gstaad, Switzerland. But Elan Jaglom told us, ‘You’re not sleeping there — that’s not the kind of upbringing I want for you.’ So while all the cousins, uncles, and my grandmother stayed in about 20 rooms at the hotel, our nuclear family stayed elsewhere."

Do you apply this philosophy to your own life?

"I have a very nice house, but the car isn’t fancy. We go to Thailand for Passover and stay at a nice hotel — but we fly economy. Passing on the values of hard work and dedication to your kids is a real challenge."

Jaglom lives in a private home in north Tel Aviv with his wife Hadas and their four children (ages 10, 8, 6, and 4). The parallels between his own upbringing and that of his children are hard to miss.

"Hadas, my wife, doesn’t come from a business family. Her father was an accountant and her mother a nurse," he says. "Just like my father, who wasn’t around much, I also mostly see the kids on weekends and during vacations. Hadas raises them day to day. That’s not easy for me — and she’s very supportive."

In what way?

"She believed in me when, starting in 2020, I spent three years searching for a company to invest in. It wasn’t easy. For most of that time — except for one year when I served as CEO of another company — I was at home.

"She’s the one raising the kids with strong values, not letting them get spoiled. I have a branch of the family that starts the morning with a joint just because there’s money in the bank. That’s not who I am."

And how did your father react when you told him about Flō?

"He told me, ‘If you want to do it, go for it — but do it yourself.’ In the end, he also invested in the company. The message he gave me was, ‘You have a safety net — you won’t end up homeless — but find your own way. Work hard, don’t be lazy, and don’t be a jerk.’ When we raised $35 million, we went to a restaurant, I gave a short speech, and that was it. No wild parties, no DJs for 100,000 shekels. I saw at Stratasys what happens when people get drunk on success. Our approach is the opposite."

Flō Optics, which employs 60 people — 10 of them in Switzerland — was founded by Claudio Rothman. The company develops printing machines for coating eyeglass lenses using a digital process. "It’s a market worth tens of billions that's still based on manual processes — dipping lenses in coating materials and drying them," explains Jaglom. "Our innovation is a machine that digitally prints functional coatings — like photochromic coatings that darken in the sun but stay clear indoors, moisture-repellent coatings, crack-resistant layers, and endless other graphics and colors. The real challenge was printing on convex surfaces down to the last pixel."

Jaglom says that the most recent funding round — which included the Italian company MEI Systems (a global leader in lens cutting), the Jaglom family, and his own private capital — was especially hard to close during wartime. "We hired new people to fill in for employees drafted into the reserves, so we wouldn’t have to fire anyone or create redundancies. At the same time, we set up a legal entity in Switzerland with 10 R&D staff. When we explained to investors that we were spreading the operational risk, it helped reassure them. I think that’s what sealed the deal," he says.

Like his father, Jonathan Jaglom was among the first investors in the newly founded Flō Optics and now serves as its CEO and chairman. "Our family’s investment philosophy is to be fully committed to one or two projects — not just financially, but operationally as well," he explains. "If you put money in, you show up and do the work."

The entrepreneur who introduced Elan Jaglom to the world of printing — and later played a key role in Jonathan’s decision to invest in Flō — was Gershon Miller. "What brought our family into printing was really my father’s journey. Elan met Gershon in the army. Gershon was a well-known entrepreneur and technologist — one of the founders of Orbotech — and they became close friends. He brought my father to Idanit (a digital printing company that was later sold to Scitex), and from there to Objet, which eventually became Stratasys. My father never expected the next generation to follow him, but Gershon was the one who helped me with the due diligence for Flō Optics. We understand printing — and that gives us an edge. For example, we were able to bring over Stratasys’ former CTO."

How has your journey with Flō affected your relationship with your father?

"Elan is a man of action — strong, educated, not really built for small talk — so the bond between us has really deepened through the work. He’s serious and introverted, but he truly believes in the company and wants me to succeed in the purest way. I think he’s proud that the legacy of involvement in printing is continuing. He speaks to me very businesslike, but through my mother I hear things like, ‘Dad’s really excited.’ She fills in what he doesn’t say. When there’s shared purpose, mutual respect, and real things to talk about, it brings our relationship to the healthiest place it’s ever been."

Beyond Flō, how do you see your future?

"I feel both a pull and a hesitation when it comes to politics. I don’t really see it in terms of right or left — I see a centrist bloc that sacrifices a lot and the need for proper leadership. After October 7, we need to treat taking responsibility as the highest civic value. You can’t fire the Chief of Staff and the head of the Shin Bet without also doing some serious soul-searching yourself. Thirty years ago, a friend of my parents asked why I — or other young people like me — don’t go into politics. He said, ‘If you don’t do it, who will?’"

That sounds a lot like what your grandmother did.

"I think she would have really looked forward to that."