This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It’s here and then it’s gone. When the run of a play or musical ends, that’s it. If you’re a movie or TV aficionado, you can always make your way back through the canon to catch up. Theatergoers make do with fragments: cast albums, the tiny percentage of shows that were filmed for television, a fuzzy YouTube clip if they’re lucky, and whatever the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts caught on tape. Plus, of course, revivals.

Much of this art form, instead, is retained in living memory, and that is finite. For example: Many performers who came up in the 1940s said that the greatest actor to ever walk onstage was Laurette Taylor, especially in The Glass Menagerie. And I hear many of you saying, “Who?” She exists almost solely in the minds of that generation, because the only filmed record of her work from the sound era is just a couple of minutes long — a screen test for a movie she didn’t end up doing. There’s barely anything else for us to see. When everyone who watched her perform is gone, the rest of us will have to take her greatness on faith.

In This Issue

For our annual “Yesteryear” issue, we asked 29 Broadway legends to pose before Mark Seliger’s camera and revisit their most memorable roles. Their careers span an enormous length of time, through multiple Broadway eras. Barbra Streisand (in Funny Girl) and Dick Van Dyke (in Bye Bye Birdie) came out of the late-golden-age productions of the 1960s. Others, like Donna McKechnie (in A Chorus Line), are from shows that carried the torch through the diminished Times Square of the ’70s. Betty Buckley, Patti LuPone, and Lea Salonga stepped into their wardrobes from the Lloyd Webber–ian British-invasion years, and Lin-Manuel Miranda and Idina Menzel recalled their arrival during Broadway’s millennial reinvention of itself. Some of these performances were career breakthroughs, turning working-stiff actors into above-the-title stars. Others were simply definitive, astonishing audiences or winning Tony Awards or creating a character that everyone knows to this day. All were roles these actors felt strongly about and were eager to inhabit in the studio. It’s likely the only time you’ll ever see most of them return to these characters. This portfolio is, like a memory of a night in a Broadway house, an artifact of a moment. — Christopher Bonanos

1964

Streisand As Fanny Brice in Funny Girl

“I wondered, ‘What if I’m not great some night?’”

Her turn as Funny Girl’s Fanny Brice, especially the showstopping song “Don’t Rain on My Parade,” all but blew the roof off the Winter Garden Theatre and fired up her career.

I didn’t know much about Fanny at first — only that she was a comedian who became a star in vaudeville. And then Goddard Lieberson, the head of Columbia Records — who had signed me to my first recording contract — gave me a transcript of interviews he had done with her for a book that was never published. I was staggered by how much we were alike, down to the colors we liked to wear. I think what I related to the most was her vulnerability. When you grow up poor, you never forget it. I still use a tea bag twice when I make tea.

But I didn’t relate to her style of broad comedy. I wanted to play serious roles — Joan of Arc, Hedda Gabler. Even though I learned early on that I could be funny, I wasn’t comfortable in some of the play’s broader bits. But you have to inhabit the character.

Once we opened, I felt trapped. This is why movies are perfect for me: You do as many takes as you need. But now I had to do a year and a half of the same performance every night. Horrendous. Of course, I was gratified by the way audiences responded. Actors I admired, like Bette Davis and Audrey Hepburn, were coming to see me. One night, I heard Greta Garbo was in the audience and I did the show basically for her.

People say success changes you, but I think it just makes you more of who you are. I’m still the same person I was then — a combination of confidence and insecurity. When the Funny Girl reviews said I was great, I wondered, What is great? And what if I’m not great some night? I was always worried about disappointing the audience.

1979

Patti LuPone As Eva Perón in Evita

“Superman got me out!”

In Evita, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s musical about the life of Eva Perón, LuPone drew on — as the lyrics go — both Evita’s and her own “little touch of star quality.”

After the audition, I went off to L.A. and did a very tiny part in Steven Spielberg’s only flop, 1941. I had to beg to be released from shooting to fly back to New York for the final callback, and I woke up to the 1978 blizzard. I got on the subway in California clothes — jeans and sneakers — and had to march through the snow to 44th Street. I was wet, I didn’t want to do this musical anyway, and now I’m compromising my position with this producer in California, so I went into the audition angry and I had to do “Buenos Aires,” “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina,” a little bit of “Rainbow High.” I did it furiously, and I left that place going, Goddamn it. I slept overnight on the airport-terminal floor, and Christopher Reeve saw me and got me on the next flight to L.A. I returned to set maybe two or three hours late, and I got applause because everyone knew that New York was shut down. They were impressed, and I told them the story: “Superman got me out!”

The pressure doing the show was excruciating. I muscled my way through. If you take a rubber band and stretch it, there’s a point where it’s the weakest. That’s the passaggio in a voice, where you negotiate your lower tones to your upper tones, and the middle is where all of the notes in Evita sat for me. I was young, and I wanted people to see who I was. Evita, the character, was intense, and it affected my work afterward — people thought I was a blonde bitch. Hal Prince — he berated me a lot, and it was painful. There was a period when Broadway creators thought the only way to get a performance was to humiliate a person. And I got them all.

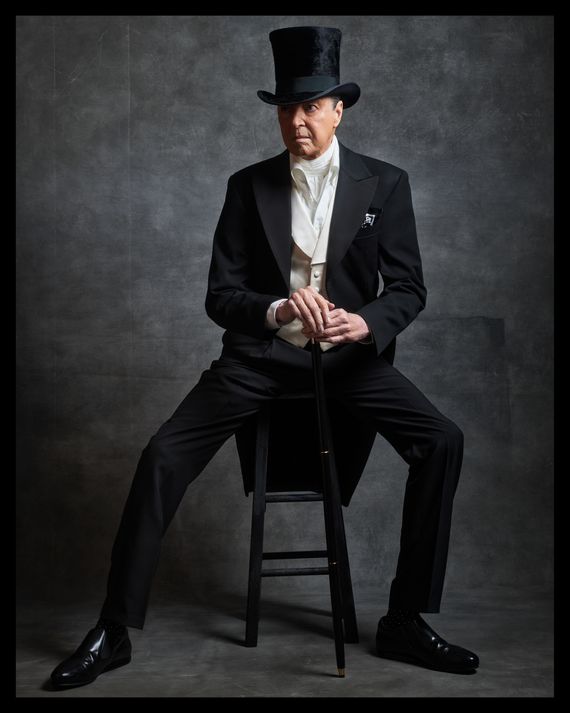

1966

Joel Grey As the Emcee

“I was disgusting!”

The sinister, arch host at Cabaret’s Kit Kat Klub, a role Grey also played in the 1972 film, guides the audience through the increasingly dire situation in Weimar Berlin.

I had no idea how to do it or what the character was going to be. I knew it would be complex and dark and funny and entertaining and terrifying — that’s all. There was no script. It was just from a conversation with John Kander and Fred Ebb and Hal Prince.

The Emcee is some poor jerk in Germany who’s all by himself, sort of a drunk and probably, you know, into other drugs. The girls all have to prove themselves to him. And then he goes home at the end of the day to milk and cookies. He has nothing of a life, except what goes on in that nightclub, and everything goes on in that nightclub. I’d worked in nightclubs before, and I hated it — all these crummy emcees who would do anything for a laugh, such creeps. One day, I said to Hal, “Let me try something at rehearsal today.” And I did. I was very lewd with all the girls, touching and feeling them — I was disgusting! And they were all looking at me like I’d lost my mind. Afterward, I went and hid behind a flat in the theater because I thought my career was over. It was so vulgar. And I was standing in the back, hiding from everybody, and Hal walked up to me, and he put his arm around me, and he said, “Joely, that’s it.” And I thought to myself, Oh my God.

Once you began the show, you never stopped. One thing led into the next, and it just got worse; it became more flamboyant and more disgusting. I became very friendly with that creep. You know, the thing that actors do is show a part of themselves, ultimately. The secret part. For better or worse.

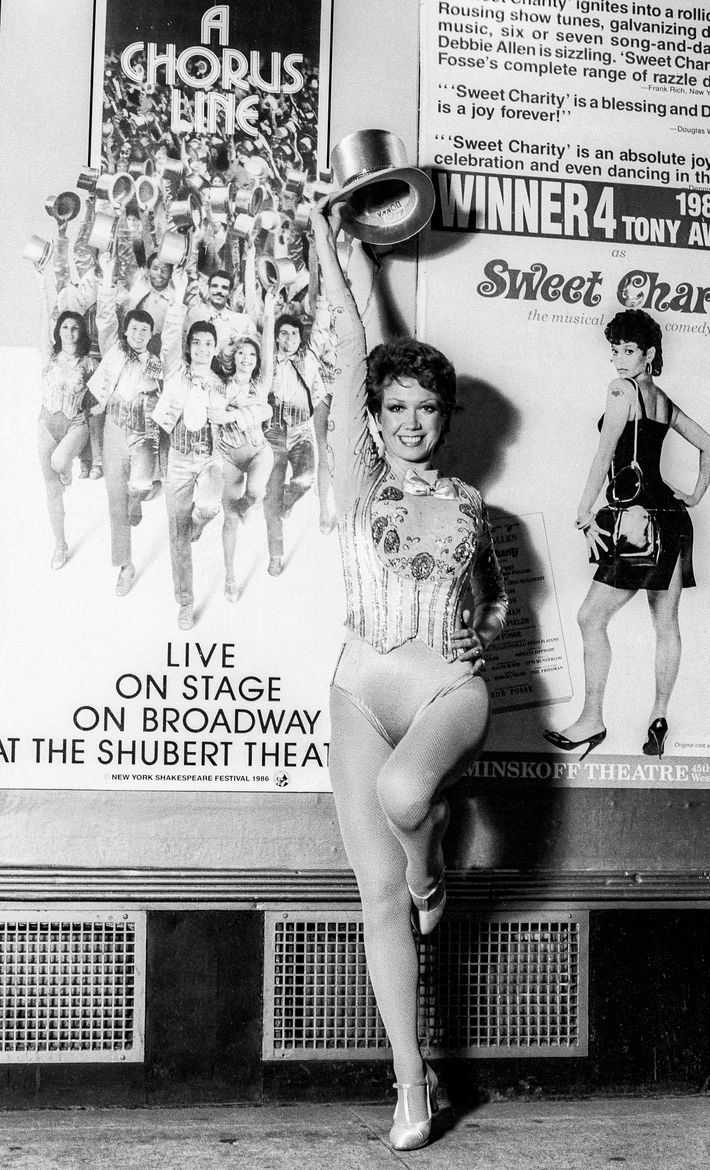

1975

Donna McKechnie As Cassie in A Chorus Line

“Everyone had their own particular secrets.”

A Chorus Line drew from real backstories recounted by Broadway dancers, with a through-line about Cassie — McKechnie’s role — and her past relationship with Zach, the onstage director character. The show ran on Broadway for almost 15 years, breaking every longevity record.

It was interesting to hear dancers speak, because dancers don’t speak. Their job is movement, and their vocabulary is dance. Michael Bennett, the director, gave us all permission to talk about the inner workings of our heart and our feelings — things people who shared the dressing rooms on Broadway shows never shared. They thought they knew each other, but everyone had their own particular secrets.

Cassie didn’t “lock in” during the first weeks, but I had that with every show I did with him. The first pass didn’t work, and he would see the failure and then he would see a way to fix it. That seemed to be our pattern. So the first time I did my big number, it was called “Inside the Music,” not the” Music and the Mirror” and it was way too ambitious — he had me singing a high C, like a soprano.

When the 2006 revival came around, there were questions about what we deserved financially from it. We sat down with the executor of Michael Bennett’s estate. I thank the dancer and choreographer Tony Stevens for that. He talked about how important it was to recognize that our contribution is still there, that all of our collaborative efforts are still in the show. He was so eloquent, everyone saw the light. It’s not much — just a fraction of a percent — but it was the principle that meant something to us.

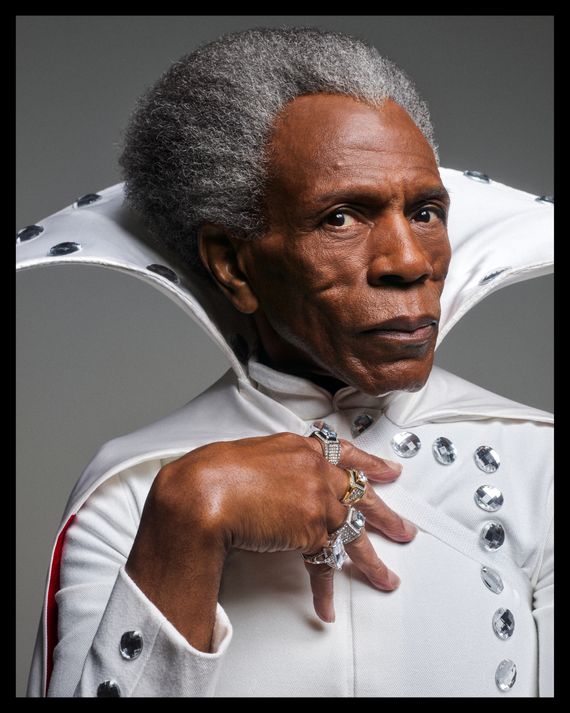

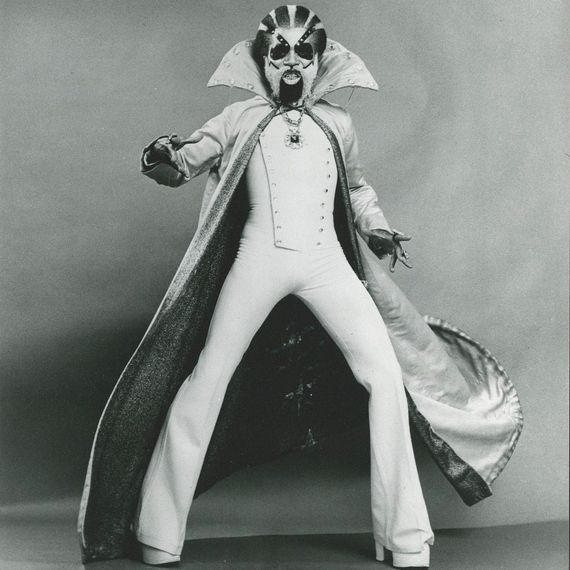

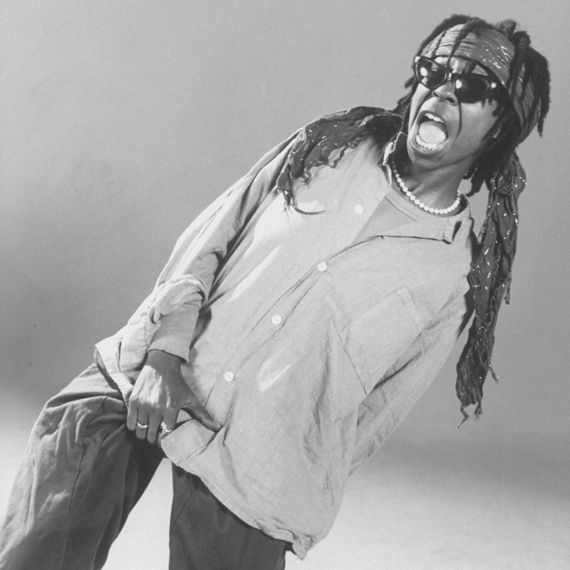

1975

André De Shields As the Wiz in The Wiz

“That’s my Wiz.”

A funk-soul adaptation of The Wizard of Oz, The Wiz was one of the first big musicals to draw Black audiences to Broadway.

The Wiz is a personality that is informed by the ’70s, which immediately followed the decade of the hippies. When I came from Chicago to New York, I was a hippie, the flowers on my bald head. I today would describe myself as an unreconstructed hippie, and that is what I invested in creating this character. Fortunately, the fashion trend was tight bell-bottom jumpsuits. It made this character the foil for Dorothy and her three friends on their visit to Oz. It also made him very attractive to the audience in an ambisexual way.

What I was doing was surrendering to my destiny to be the Wiz — to be the actor who would essay the title role. And that’s why I begged for an opportunity to audition: because I knew I was the chosen one. I mean, people have illusions of self-grandeur all the time, but I was following what I knew to be a destiny. I initially auditioned as the Scarecrow, and I was cut. Then they allowed me to audition for the Lion, and I was cut. They allowed me to audition for the Tin Man, and I was cut a third time. And this is what I did — which doesn’t happen any longer.

First of all, the auditions were held in the Majestic Theatre, the theater that we would later open in. Nowadays, you audition in a clinical studio with bright lights, and you’re trying to catch the attention of a group of people who are eating their tuna-fish sandwiches. At the Majestic, it was dark. You could just barely make out the silhouettes of the people who were evaluating your audition, and when you were brought from the wings, you would hear your footsteps echoing. I said to Ken Harper, who was the producer — and, of course, I’m calling him “Mr. Harper” at the time — “I really want to be the Wiz. Will you let me audition for the Wiz?” He explained to me then that they were looking for someone similar to Frank Morgan, who played the wizard in the film. I begged him, and he relented. I came back for that audition, and I thought, Okay, I’m not going to get cut this time — I’m going to blow them away.

Now remember, I’m a hippie coming in from Chicago. I put on my five-inch silver platform shoes. I put on my blue hot pants that had L-O-V-E stenciled across them. I put on my red halter shirt, which had L-O-V-E stenciled across it. I went in and sang Wilson Pickett’s “In the Midnight Hour.” At the end of that song, Charlie Smalls, the composer of the music, rest his soul, stood up in the darkened house and said, “That’s my Wiz.”

Ken Harper was one of the first producers to invest in live-action commercials on television. He was smart. He reached into the homes of the people who were being reflected in The Wiz but who had experienced inhospitality on the terrain that we know as the Great White Way and gave them a message: “Get off your Black butts. Don’t become a couch potato. There’s something happening on Broadway about you. Come see it.” And people did, and from that, the momentum built.

We’re still working on a place in the canon of American musical literature for The Wiz. It got a raw deal in what I consider an ill-conceived film version, and it was tinkered with too much in the television version. And the recent revival was so spare it wasn’t reminiscent of The Wiz from ’75, which was so classy. As long as I’m breathing, I’m going to continue dispelling those mediocre experiments with The Wiz and remind people of the game-changing glory, glamour, and grace of the original production.

1992

Nathan Lane As Nathan Detroit in Guys and Dolls

“If I try any harder, there’s going to be internal bleeding.”

Lane — who as a young actor took his stage name from this very character — redefined the role of Damon Runyon’s craps-playing operator, Nathan Detroit, in the 1992 revival of Guys and Dolls.

Guys and Dolls hadn’t been done on Broadway since 1976, and it was a big deal they were going to do it again. It’s the quintessential New York musical comedy. Everybody pretty much said to you, “Don’t fuck it up!” I heard there were a lot of people going in for Nathan Detroit, but according to the director, Jerry Zaks, I was the funniest guy to read for it. Everyone kept bringing up the fact that I wasn’t Jewish. He was like, “Yeah, I know it was written for Sam Levene, who was Jewish, but this guy is really funny.” Now I’m an honorary Jew! I’ve played more Jewish characters than any other kind. Somewhere along the way, I got a pass. It all started with Nathan Detroit.

Even though it was great material, that production took a while to figure out the right tone. After we finished one night, Jerry called us out and said there had been walkouts at intermission. He said, “I don’t think you’re trying hard enough.” I said, “Really? Because if I try any harder, there’s going to be internal bleeding.”

Now, a lot of people will say to me that it was the first show they saw as a kid, which makes you feel old, but they talk about it in such reverential terms. I did the show again for one night at Carnegie Hall back in 2014, and I was so much better so many years later! I just understood more about everything — life, and the show itself.

1996

Bebe Neuwirth As Velma Kelly in Chicago

“There was a metaphysical bond.”

A modest success during its first run in 1975, Chicago — with its array of cheerful, murderous characters dancing to slinky Bob Fosse choreography — was restaged to huge acclaim two decades later, starring Neuwirth and Ann Reinking and directed by Walter Bobbie. It’s still running.

There was an alchemy to this cast that Annie and Walter put together — one of those somewhat rare occasions where the sum was greater than the parts. We were a cast who almost all knew each other, and if we didn’t, we were connected in some other way. There were personal alliances; there were best friends; there were husbands, wives, ex-lovers, ex-husbands. Except for maybe two people, we had all worked directly with Bob Fosse and Gwen Verdon, and there was a metaphysical bond between all of us.

I had known Annie for a while. We got so close doing this. Words fail me because she was my partner. She said, “We’re like salt and pepper, but I don’t know which is which.” When we danced together, our connection made us more than a couple of great dancers wiggling together.

This show had a profound effect on my entire life, and it’s not just the shoulder injury that I still feel from it, from holding on to the ladder all those nights. I recall telling myself to remember the feeling that I had when I was on the stage doing that show and to remember what it felt like when I was performing “I Can’t Do It Alone” with Annie. Just remember what it felt like to feel the wind on my face as I traveled around the stage. I’m so grateful to my little 37-year-old self that I had the presence of mind to do that, because, boy, there was nothing like that.

1972

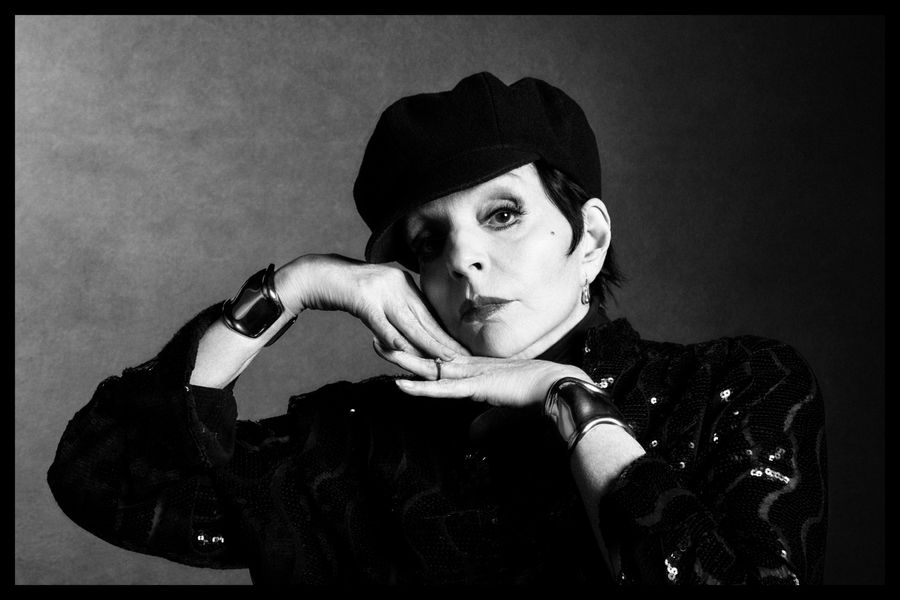

Liza Minnelli As Herself in Liza With a “Z”

“I want to be buried in Halston — no cremation, baby!”

Liza With a “Z,” her one-nighter at the Lyceum Theatre with songs by John Kander and Fred Ebb and choreography by Bob Fosse, became one of the greatest concert films ever made.

You can’t speak about my past without celebrating John Kander and Fred Ebb. They understood that I was desperately trying to carve my own lane. It gave me an opportunity for people to know me outside of my parents and outside of Sally Bowles. I didn’t have hit records, but Liza With a “Z” gave me the equivalent of multiple hits. And I’ve always said Bob Fosse knew everything about me and used every single part of my body, including my scoliosis. Everybody wanted to know: Did we or didn’t we? I’ll just keep you guessing.

There were more moods in rehearsal than there are colors in any rainbow. We were happy. We were sad. We were frustrated. We were exhausted. There were tears and — something I hate — there was a little bit of shouting. Although I’d been around TV forever, most of these great artists had not. When we got down to the last minute, everybody was worried about it and so tired. When it was over, I had one overwhelming thought: The material was great. The artistic team, amazing. But was I any good? When I see it today, I’m proud of everybody. And finally, I realized I was okay.

We were hiding from the censors how sexy that red sequined dress was gonna be. How far could we go? How short could we get it? I saw sponsors and network people all clutching their chests, but nobody died. Halston was such a genius — decades later, I still wear his clothes all the time. I want to be buried in Halston, but no cremation, baby — why ruin an exquisite outfit?

2001

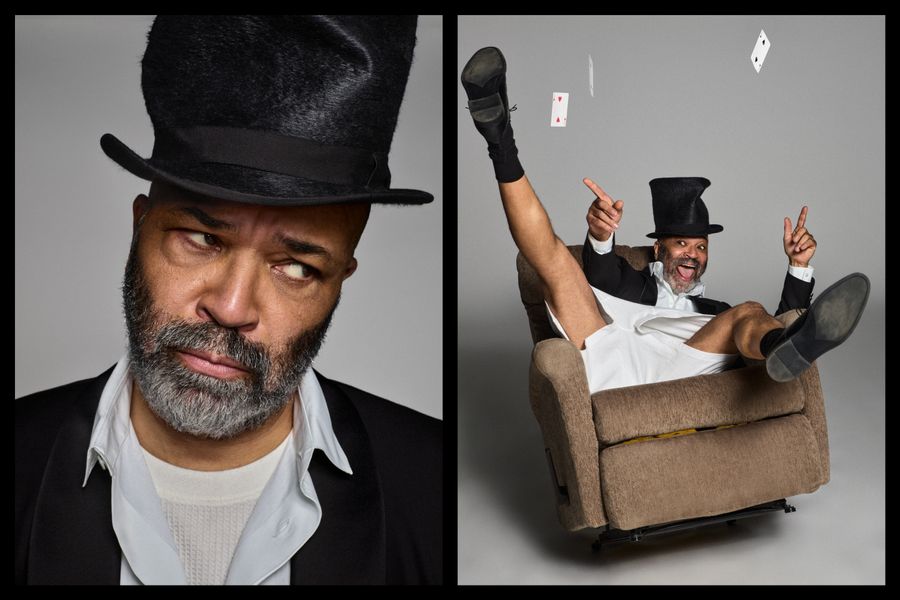

Jeffrey Wright As Lincoln in Topdog / Underdog

“I found myself saying ‘Don’t fall over.’”

In Suzan-Lori Parks’s Topdog/Underdog, Wright played a man, living with his card-hustler brother, who works as an Abraham Lincoln impersonator in an arcade where he’s mock-assassinated every day.

I was always curious about those games that used to exist on Manhattan street corners, and I’d watch those cardboard tables disappear and some German tourists standing there empty-handed. Suzan-Lori Parks’s husband at the time was a guy named Paul Oscher, and he had played three-card monte, so Suzan knew the logistics and the psychology of the game. He helped transfer as much of that ability onto me as he could.

I’d done Angels in America, which was a seven-hour play, and Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk, and the pace and energy of that show was super-high. Topdog is only two and a half hours, but it’s two people onstage hyperfocused on each another. It was a real test. There were some nights when I just couldn’t conjure it. While I was doing the play, I was filming Angels in America for HBO, and my son was about 2. There were a few evenings when I showed up at the theater after having filmed all day, not having slept much the night before, and I literally found myself onstage saying, Don’t fall over. I didn’t think those performances were optimal.

Our audiences were responsive, and sometimes we would have folks sitting in the front of the audience passing food to one another, picnicking. I remember one night there was a group in front, about six of ’em together, and at the end of the play, the moment comes when the hammer drops on Lincoln and the lights fall. And before the applause started, I heard this woman say, “He shot his brother!” I just lost it. She was so surprised and appalled and intrigued. She was fully there.

1984

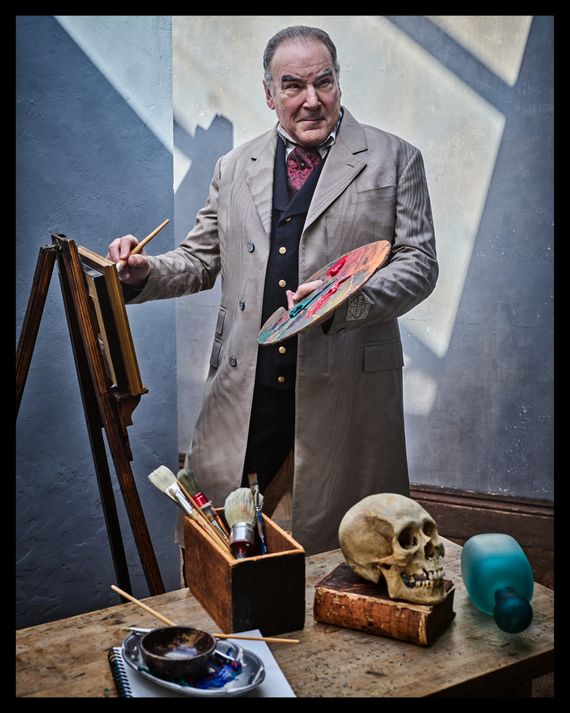

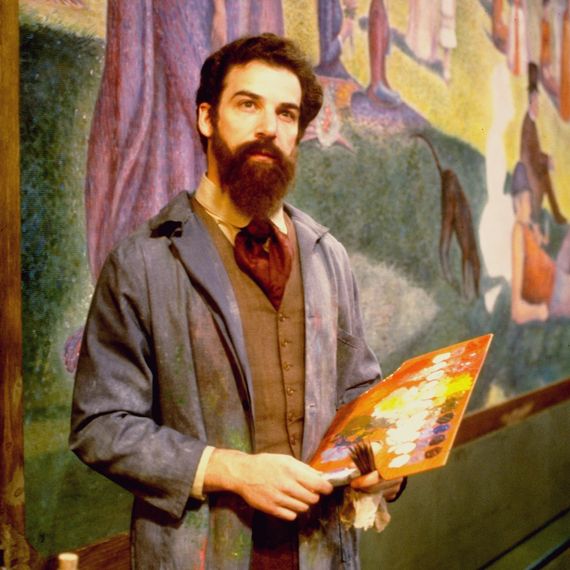

Mandy Patinkin As George in Sunday in the Park With George

“Every night, I would draw Bernadette.”

In Sunday in the Park With George, Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s masterwork about the art of making art, Patinkin played both Georges Seurat in 1884 and his artist great-grandson a century later.

James said, “Do you draw?” My father always used to make a joke about how he could draw a box, where you draw one box and then you put the other box inside and then you connect the four lines.” I said proudly, “Well, that’s all I can draw.”

He said, “Would you be willing to go to the Art Students League and take some classes?” I said “sure,” so I went and loved it, and sat there and got lessons, particularly in Conté crayon, because that’s what Seurat often drew in. Those are my favorite things he ever made, especially the one of the little girl who ended up in the painting, because it’s almost a white page; there’s hardly a line on it.

I would sit in rehearsals, and every night, I would draw Bernadette on my easel pad in the very first scene when she sang “Sunday in the Park With George.” My dresser, James Nadeau, saved every sketch pad, and he gave them to my wife, unbeknownst to me. She had them bound in a gorgeous book, and I occasionally take one out and give it to somebody as a gift.

At that time, they were working on the first act. That’s all we had. I was freaked out because I wasn’t an improviser. We’re doing a run-through, and a lot of my stuff isn’t written. In the scene where I sit with my mother and she sings about life being beautiful, I started weeping. I went, Let it go — let it wash it all out of you. And Steve came up to me afterward, and he said, “I’d love to talk to you about the mother scene.” I said, “Well, first of all, he shouldn’t be crying. I was just trying to clean out my nerves.”

2024

Audra McDonald As Madam Rose in Gypsy

“I finally figured it out: ‘Oh, she’s leaving me.’”

Gypsy’s Madam Rose, the King Lear of musical-theater roles, requires just about everything a performer has, especially in the immense closing number, “Rose’s Turn.”

I started singing “Rose’s Turn” in concert a couple of years ago, just to see if I could. I’d had an experience with my older daughter the summer before she went off to college. I was snippy and couldn’t figure out where this irrational rage was coming from. Then I finally figured it out: It’s because, oh, she’s leaving me. She’s going to live her life. Even though that’s what you prepare your children for, so that they can walk away. But the weird sort of abandonment I was starting to feel — I channeled that into singing “Rose’s Turn” in a couple of concerts. That was the beginning of my understanding of Rose. Once I figured it out, then I was fine. Then the rage went away. I was overwhelmingly proud of her and excited for her to start this journey. Then I was crying all the time.

Rose is an amalgam of so many women in my life, in my ancestry — I’m not saying any of them are as extreme as Rose, but that fierce love, loyalty, determination that your children are going to have better than you had, especially coming through a Black lens. My mother’s family had to use the Green Book when they’d travel from Virginia to Chicago to visit her aunt in the summer. I look at Rose getting her kids to a place of fame and notoriety as a way of protecting them. She’s not going to abandon her children — that ends with her mother. She’s trying to stop that generational trauma.

1982

Betty Buckley As Grizabella in Cats

“I cannot turn a cartwheel to save my life.”

She sang the definitive version of “Memory,” one of the most recognizable show tunes ever, in Cats.

The whole eight-week rehearsal period was one of the greatest experiences of all of our lives. Cats had some of the greatest dancers Broadway has ever seen, but there were five of us who couldn’t really dance. One day, we had to do turns across the floor and cartwheels, and I cannot turn a cartwheel to save my life — it was a nightmare. There was a lot of laughter and humiliation involved. Then we’d do improv exercises. My cat at home spent a lot of time sleeping in the sun, so I’d curl up in the front of the rehearsal studio and nap while all the other cats were doing all these crazy things.

Finally, we did the first run-through, and everyone had forgotten why I was in the show — all they knew of me was that I couldn’t turn cartwheels and I was always napping in the corner. Trevor Nunn, the director, had deftly set up the rehearsals so I was the outcast of the tribe, like Grizabella. Then when she sings “Memory,” their hearts are touched, and she gets picked to go to the Heaviside Layer.

Lots of cats had faces that were really complex, but mine was basically just a charcoal sketch, then red lipstick that I smeared. I could go from being in my winter coat to having full cat makeup and costume on — we timed it, me and my dresser, Marcie Olivi — in nine minutes flat. Sometimes I would lollygag in, and people started getting mad at me. I was like, “You guys, it only takes me nine minutes!” The joke was that I would just toss my makeup in the air and run under it. So people placed bets and there ended up being this huge pot of money, and one night they timed me. Marcie and I won.

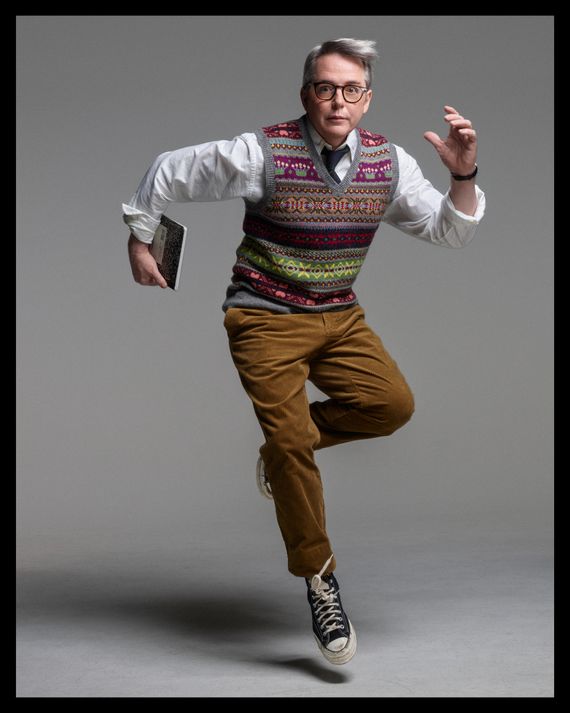

1982

Matthew Broderick As Eugene Morris Jerome in Brighton Beach Memoirs

“Neil’s note was to stop that.”

Broderick played a 1930s teenager in Neil Simon’s Brighton Beach Memoirs, then returned to the role in the sequel, Biloxi Blues, two years later.

I was 19 when I was cast. In rehearsals, Neil sat at a table with the director, Gene Saks, and if you did something that you could tell didn’t work great, you would see him lean over and whisper something in Gene’s ear and then you’d get a note: “Don’t do that.” “Don’t pause.” “Do pause.” He was mercurial, in a way. He was very shy, but he could go right from “Oh my God, this is not working” to “This is hilarious and I love you” in a very short time.

In the part, I talked to the audience, so I had lots of these little paragraphs of monologues. One night, Neil came in and he was very happy, mostly, but he said, “When you make a mistake” — because I would mess them up a little bit — “I don’t really mind that, but I don’t think you should say, ‘Oh, wait, that’s not right.’ I don’t think I’ve ever seen anybody do that.” Apparently, when I would make a mistake, it was very hard for me to not say, “No, that’s not right,” and go back. So his note was to stop that.

There’s a scene early on where my brother, played by Željko Ivanek, has a long monologue. A few months into the run, Željko forgot his lines really badly. So he looked to me to help him out. He even grabbed me like a hug, and I realized he wanted me to say what’s up next. And I said, “I don’t know. I don’t remember.” I remember a stage manager creeping around the edge of the stage with a script to try to help us get out of it. It was absolutely terrifying. I went into the greenroom after to commiserate with Željko, and he was just lying on his back on a couch, almost comatose.

1982

Harvey Fierstein As Arnold Beckoff in Torch Song Trilogy

“Originally, the gay men came in disguise.”

Fierstein wrote and starred in Torch Song Trilogy, an early mainstream depiction of gay relationships without stereotypes of self-destruction.

You have to remember what year it was when I was doing a play on a Broadway stage about getting fucked up the ass. Gay people came to see our show, but they came with women, in disguise. The scene in the back room, where my character is in a bar getting fucked, was scary to the audience. I was being interviewed as if I were from another planet, as if I were the first gay person on Broadway. I had to constantly think about, Is that one out? I used to tell reporters that if you saw me with someone, then no, they’re not gay. Cher I could have dinner with in public. Rock Hudson and I did not have dinner in public.

There was a restaurant called Ted Hook’s Backstage where we spent many drunken nights — obviously, before I got sober — Chita Rivera and Anne Meara and I. One night, Debbie Reynolds got up to the piano and did her nightclub act. I left at 4:30 in the morning. The next day I put on the TV and there was a report that Debbie had been taken ill to the hospital. I called her daughter, Carrie, and said, “Don’t worry about it. It’s just a hangover.”

It was freaky for me when they did the revival of Torch Song in 2017. Originally, the gay men came in disguise. When we did it again, they came to the theater owning the show. There was no shock to the back-room scene. They knew every joke, every one of the mother’s lines. It was lovely because they had taken ownership of it. But also it lost that surprise.

The bunny slippers I wore in the show are in the Smithsonian. I made every pair for every understudy, every company, hand-crocheted, until I couldn’t keep up anymore.

2000

Mary-Louise Parker As Catherine in Proof

“I regretted having left when I did.”

Parker, as the daughter of a recently deceased mathematician, delivers a huge twist at the first-act curtain, claiming authorship of one of his works. Her last performance in Proof was two days before 9/11.

I was set to do another play directly after Proof, and I said to my agent, “What if this play transfers to Broadway?” He said, “Oh, this isn’t the kind of play that’s going to transfer.” It’s deceptive, that play. It feels simple. I oddly didn’t anticipate people enjoying it. I thought, People are going to hate this woman, but this is the only way I know how to do it.

Off Broadway, the first couple of weeks, the ending wasn’t really working. The lights went down one time, and this older person in the front row went, “Is that it?” Once it got to Broadway, it was in the right shape. When everybody’s aligned and the audience is really listening, it’s pretty hard to beat that.

If we went out, we’d go to Joe Allen. I liked to go home; I used to go out the back of the theater. I get awkward, and I don’t know what to say, especially after a play. I can be kind of a loose cannon. I don’t want to subject anybody to it. I worry if I run into people if I was nice enough or if I said “thank you” enough to their compliments.

I regretted having left when I did. One time, I was on a plane and this woman next to me said, “I’m so excited. I’m going to see Proof.” My heart sank — I had left the show six months earlier. But then she said, “I read about it. And I heard this girl” — meaning me — “is really great.” I felt a little bit better after that. I realized that that’s what happens when you set up a play. It’s like getting a boyfriend ready for his next relationship. You did all that work for whoever is next.

1983

Tommy Tune As Billy Buck Chandler in My One and Only

“But I’m in the show — how can I direct the show?”

Tune was already acting in and choreographing My One and Only, a new musical made up of Gershwin tunes — then stepped up as director. The show won him two (of his ten) Tony Awards.

We had a really bad birth in Boston, and they came to me and they said, “We’re going to fire the director. We want you to take over.” I said, “But I’m in the show — how can I direct the show?” And they said, “You take over the direction of this show or we’re closing it.” So I said “okay.” I called in everybody I knew, including Mike Nichols, who was hugely helpful. I would play on the stage with everybody and get it set and then I would run out front and have them do it without me. And then I’d run back in and fix it. And then Mike would take a look at it and fix it further. It was really hard, but we had that great Gershwin music to see us through.

Twiggy and I were playing opposite each other, and I was teaching her to tap-dance, and she was learning great — she was a good student. But she was an unseasoned stage performer, so it was my job to protect her. She was frightened, but she never let it get her down. She was especially good in the water dance — we slid down into a trap of water across the whole stage and did a big tap dance in the water. Some London producers said, “We’d love to do the show, and we’d like to fly you over for the queen’s birthday, and if you could do the water dance, it would be terrific.” We got on the Concorde after our last show that week, jetted to London, met the queen, did the dance, got on the Concorde, and came back. We were late getting back to the theater, and people were waiting out on the sidewalk. When we got out of the cab, everybody clapped, and we said, “Just give us a few minutes to put on the costumes, and we’ll be out with you.”

1984

Whoopi Goldberg As Fontaine in Whoopi Goldberg

“I always liked it when he said ‘Ms. Goldberg.’”

Whoopi Goldberg, the solo show in which she embodied multiple characters — a junkie, a surfer chick, a little girl who imagines having “long, luxurious blonde hair” — vaulted Goldberg into fame and was filmed for HBO.

At the Dance Theater Workshop on 19th Street, the first night there were maybe three people who came and the second night maybe six. That weekend, Mel Gussow, the New York Times critic, came. He wrote an amazing review — it was like he was my boyfriend. The next thing you know, there were all kinds of people coming. I used to bring my mom every night, and one night she said, “I don’t want to tell you this, but you should know Mike Nichols is in the audience.” He got me. He didn’t think I was weird. That was the first time anybody had ever been able to break down for me what I was doing without me having to explain it to them.

He offered to bring the show to Broadway. I’d thought he was kidding, just being nice. I had finished the show at DTW, and I’m back in Berkeley, and the phone rings, and he says, “Ms. Goldberg? I found a theater.” And I said, “For what?” Eventually, I was able to call him Mike, but I always liked it when he said “Ms. Goldberg.”

He opened the world to me. He’d say, “I’m having lunch with Paul, Carl, and Steve,” and then I walk in and think to myself, Oh my God, that’s Paul Simon, Carl Reiner, and Steve Martin. I got to spend time with these folks and really talk about their art — if Mike Nichols brought me in, I know I’m good. That was important, because people haven’t always understood why I am where I am. “How did you get here? Why you?” Because somebody thought I was good enough.

1975

Rita Moreno As Googie Gomez in The Ritz

“I mooned him once.”

In Terrence McNally’s The Ritz, a farce set in a gay club not unlike the Continental Baths, Moreno plays Googie Gomez, an outrageous singer with dreams of stardom.

The only thing that’s really funny about Googie is her sincerity, her belief that nobody is as talented as she is — and of course she has no talent whatsoever. It was a thing I made up based on a Puerto Rican singer I thought was hilarious. I won’t mention her name, but a lot of Puerto Ricans knew who I was doing. I was doing a Broadway show with Jimmy Coco called Last of the Red Hot Lovers, and I used to do the Googie voice backstage just for fun. One time, he invited me to a party with Terrence McNally, who was a good friend of his, and Jimmy took us to the bedroom and told me to do her, and I did “The Song of Hiawatha” and the “Player King” speech from Hamlet, and Terrence was just falling off the bed laughing. When Terrence left that evening, he told me he was going to write a part for that character. A few months later, Jimmy stops me on the street and says, “Did you get the script yet?”

I just adored playing her on Broadway. It never occurred to me that any Hispanic person would be offended — as a matter of fact, I never got anything from anybody about “Shame on you.” I could never get away with that now — I don’t know if you could do The Ritz. Well, maybe.

Jack Weston was an insanely funny comic actor, and he and I just hit it off like crazy. I was always trying to make him break — I mooned him once when he was doing a crossover, and I thought he would have a heart attack. We had a seduction scene, and I would always try to get further than he expected, unbuttoning his shirt and undoing his belt so his pants would fall down. We were so full of the devil, and it never stopped, because the play was so damn funny. The stage crew adored Googie, and their favorite line was “piece of shit,” which she pronounced like “piss of CHIT.” They were always doing that line for me.

I won the Tony for Best Supporting Actress, and in my speech at the Tonys I said that I’m not a supporting actress. As Googie, I said, “The only thing I support in my show is my beads.” The audience loved it, but the producer of the Tonys, Alexander Cohen, was furious. He hated me. He was not a nice man. He said, “You will never do the Tonys again.” And I didn’t as long as he was in charge. I should have been invited the next year to give a Tony to somebody, but no, no, no.

There were lots of gay people who came to see The Ritz, needless to say. They kept the show running. There are still so many gay guys I run into who tell me they love Googie. Andy Warhol showed up one night. Barry Manilow came because he used to play the piano for Bette Midler at the baths. One absolutely wonderful thing was at my closing night — we’d been doing it for a year, and I was exhausted. Every gay person that lived in New York was there, and at the curtain call, this row of men holding bouquets came up to the stage and laid them on my feet. I’ll never forget that as long as I live. I had my little daughter onstage with me, and she said, “Why are they doing that?” I said, “Because they love me, and they don’t want me to leave!” We took all these bouquets home to our apartment, and they were everywhere. They were in the toilets. You had to take out at least five bouquets if you wanted to pee.

2008

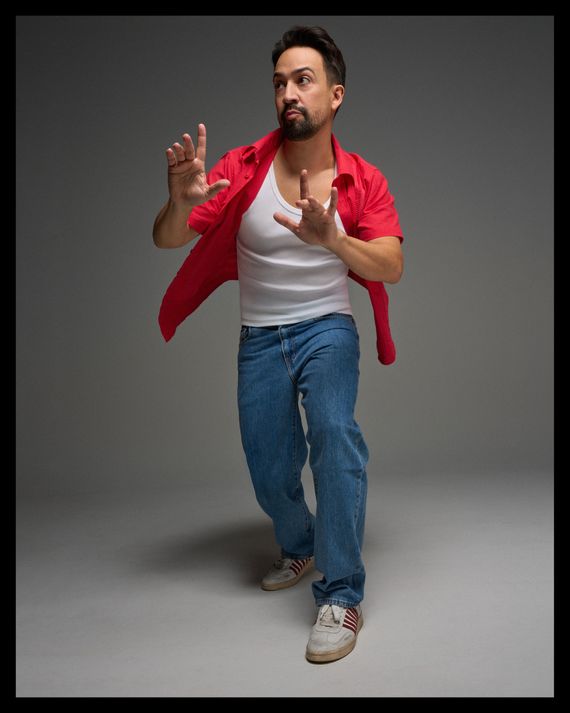

Lin-Manuel Miranda As Usnavi in In the Heights

“Play it for now, and we’ll find a real actor later.”

When he was just 28 — seven years before Hamilton — Miranda co-wrote and co-starred in In the Heights, which won Best Musical at the Tonys.

In my college 80-minute one-act version of In the Heights, Usnavi was comic relief — kind of the third friend. And one of the first things the director, Tommy Kail, said to me was, “Everyone in the neighborhood goes to Usnavi’s store, so does it make sense for him to be a narrator character, welcoming us into the world?” That’s when he slowly turned from Ross on Friends to Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof. I took that first draft as far as it could go on my own and with Tommy, and I realized I needed help. We were very lucky to meet Quiara Alegría Hudes, who took on librettist duty, and then we basically wrote a new show from scratch. She deserves the credit for making the show more about the neighborhood and the community.

When Tommy and I began working together, it was easier for me to play Usnavi than to teach the character with the most hip-hop lyrics to an actor when we only had a 29-hour Equity reading contract. So Tommy was like, “Play it for now, and we’ll find a real actor later.” And that never happened. The producers who eventually signed on — Kevin McCollum, Jeffrey Seller, and Jill Furman — were like, “We don’t know what the story is, but we like you as the narrator.” So I kind of became a part of the package, started playing it in readings and workshops, and ended up staying in it. And then when Corbin Bleu went into the role, he was like, “Yeah, it’s tricky because Usnavi’s such a bad dancer and I’m a trained dancer!” I was doing my best, man!

1991

Lea Salonga As Kim in Miss Saigon

“Demonstrators barged into the mezzanine.”

Miss Saigon drew fire over its casting of Jonathan Pryce in yellowface, but Salonga’s performance as a Vietnamese bar hostess who falls in love with a U.S. Marine (Simon Bowman in London, Willy Falk in New York) won her nearly every award there was to win, including an Olivier and a Tony.

I was 18, and I was woefully inexperienced with a lot of things. It took director Nick Hytner actually demonstrating what those things were and what the expectation from me was for me to get it. I had to watch him make out — ish — with somebody. Not in a weird, creepy, icky way — he just needed to jump-start my brain. It was not enough for him to verbally say, “I need passion. I need sex. I need romance.” I did not understand that. But the minute he got into the bed with Simon Bowman and put his hands all over him, I’m like, “Okay, now I understand.”

As far as the emotion, the Vietnam War had ended maybe 15 years prior. It was still very fresh in a lot of people’s minds. Are they going to feel anger, guilt — especially an American audience? There’s going to be all these conflicting feelings. My job was to move the audience, and they can project whatever their emotions are onto me.

Sure, the show has had its controversy with regards to its casting: During previews, demonstrators barged into the mezzanine while we were onstage. I got distracted for maybe five seconds and just tried to stay focused on why I was there. And over time, Miss Saigon did score a win in that, after Jonathan Pryce had left the show, only Asian actors got to play that role. Now they’re coming correct, to use the modern parlance.

1978

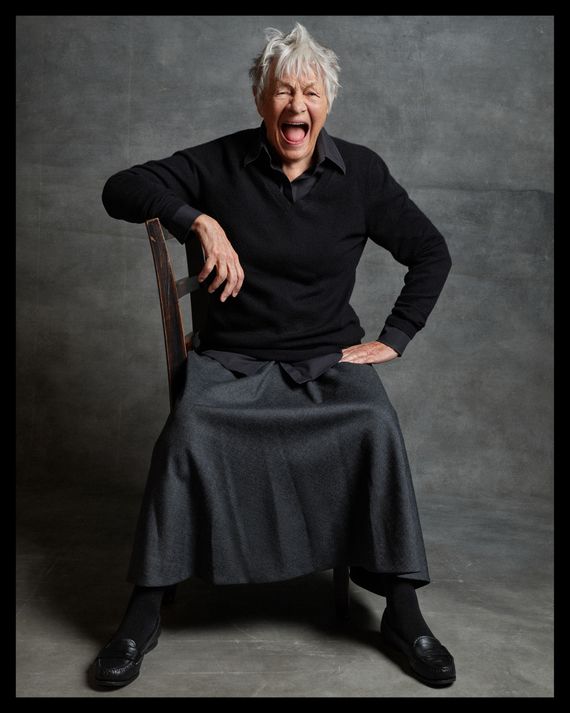

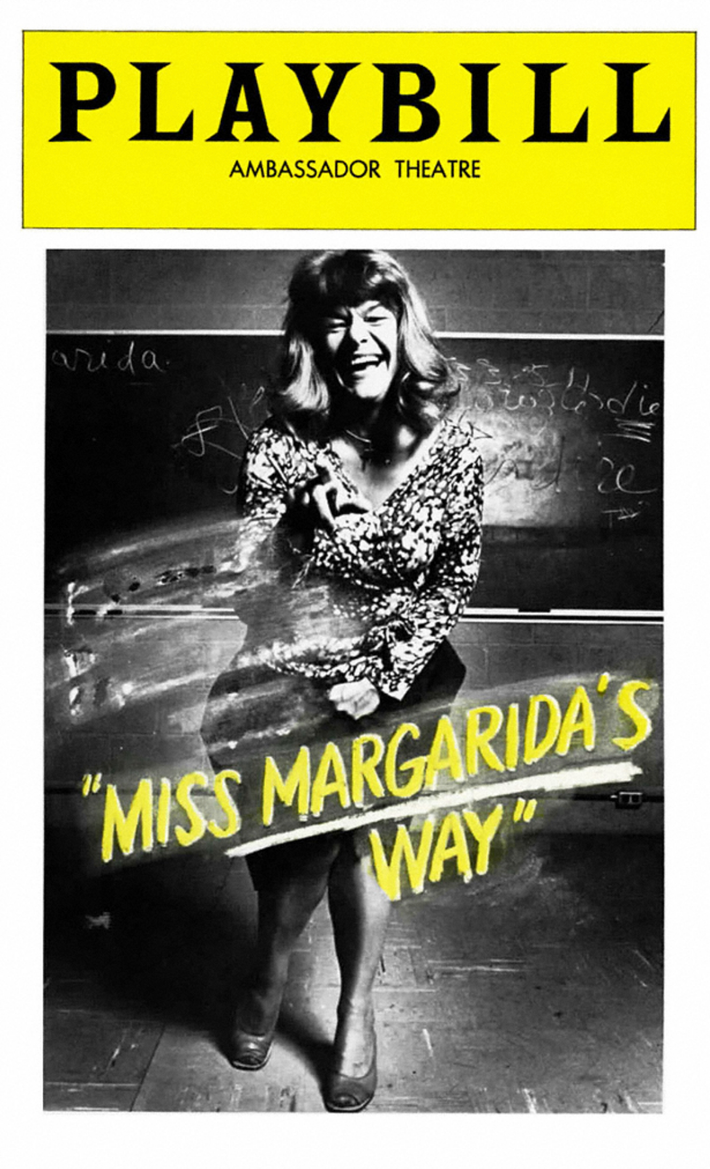

Estelle Parsons As Miss Margarida in Miss Margarida’s Way

“I would be afraid to do this play now.”

In Miss Margarida’s Way, Roberto Athayde’s unusual Brazilian play about totalitarianism, Parsons starred as the titular teacher, who repeatedly interacts with audience members as if they were unruly pupils.

I was being interviewed by this French guy, and he said, “I think you’d be interested in this play that I’m doing — it’s to the audience.” He sent it to me in French, and I was able to read enough to know that it was very interesting. Roberto Athayde wanted to direct it, but nobody wanted to work with him — he was very volatile — and I thought, Well, I usually have a good relationship with playwrights.

Roberto said, “We have to have an audience for the rehearsals. You can’t rehearse this play in an empty room.” So the stage manager went around and put up signs saying FREE SHOW, and the place filled up. I was just reading the play off the page, and people just loved it. Joe Papp, from the Public Theater, came in after about four weeks, which is the rehearsal time you usually have to put up a play, and he said, “Boy, you’re not ready. You probably need another three weeks.” Which I did.

Roberto had said, “Listen, as soon as you come out there and say you’re their eighth-grade teacher, they fall right back into being students.” And of course, we were rolling our eyes. But when I said I was the eighth-grade teacher and asked a question, this woman raised her hand and I called on her — and she got so upset! But if anybody upset the show too much, as some guy did one night — he kept heckling me — the whole audience would turn on them. Once, I came back from the intermission and there were 32 people onstage. People have said to me, “Why don’t you redo it?” But I would be afraid to do this play now. People were more civilized then.

2025

Bernadette Peters As Sondheim’s Women in Stephen Sondheim’s Old Friends

“You follow the map and be as truthful as you can.”

In Stephen Sondheim’s Old Friends, a revue opening April 8, Peters leads a celebration of the master songwriter’s craft.

When I’m singing “Not a Day Goes By,” I’m thinking about Steve. There are two versions of that song in Merrily We Roll Along: a happy version and a sad version. The happy version, you’d call it, is not quite happy but more involved with love or involved with the perfect. I’ve always sung the sad version in concert, so now I have to relearn the lyrics.

When he wrote, he really thought of all the best choices for character — each show had its own persona, and each character had its own persona. He knows deeply what the character’s going through, so you follow the map, so to speak, and be as truthful as you can. Even technically, he understood holding a note on a certain vowel is more important than giving a vowel that you’re going to swallow and gargle. Because his words are so well chosen — not the norm now — people really appreciate that he’s become our Shakespeare of musical theater.

When I was in Sunday in the Park With George, the first number he had for us was “Color and Light,” where Mandy Patinkin is painting and I’m powdering and it’s a back-and-forth, and I went, Oh, I just love this. He was very kind to actors. I remember once when I was singing “Children Will Listen” in Into the Woods, I forgot the lyric. Steve was there. He came backstage and the first thing he said was “Oh my God, I couldn’t get up there on the stage in front of people and do what you are doing.” He was just so kind about it.

1969

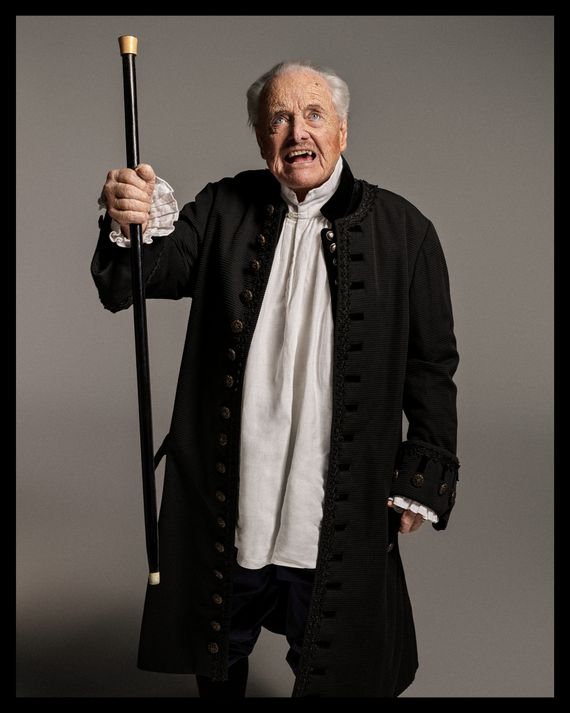

William Daniels As John Adams in 1776

“I forgot the lyrics. They laughed. I didn’t laugh.”

Before he was Mr. Feeny on Boy Meets World, or St. Elsewhere’s Dr. Craig, or the voice of Knight Rider’s KITT, Daniels played a Founding Father in 1776 — at the same theater that’s now home to Hamilton.

The audition? I blew the lyric of a song I knew. And I went to the wrong theater: Nobody’s here. I think I’ll go home. But my sense said, You’d better call your agent. And she said, “They’re not at that theater; they’re at this other theater. Get over there!”

So by the time I got in, they were all waiting for me. I sang a little song, “Wait Till We’re Sixty-Five,” from On a Clear Day You Can See Forever. I forgot the lyrics. They laughed. I didn’t laugh; I was embarrassed. But I think they had it in their minds that they were interested in me doing the role. It was not so much an audition as they wanted to hear if I could sing it. Well, I’ve been singing since I was a kid, so that was okay.

John Adams was my most challenging part. Not anybody else, not Mr. Feeny. First of all, I didn’t look anywhere near like him. I did background, went and read quite a bit about John and Abigail Adams. But I had my doubts about what this was going to be. I was negative about so many things. And then I heard the chorus sing, “Sit down, John. Sit down, John. For God’s sake, John, sit down!” I thought to myself, Maybe we got something here. Idiot! And we were off and running, and I did it for two years and two months.

I met Lin-Manuel Miranda at a performance of Hamilton. He wanted to know, “Where was your dressing room?” So I said, “Stage left.” He said, “No, can’t be.” I said, “No, come, I’ll show you.” And I took him to the room, and it all had changed. It wasn’t a dressing room any longer — the electricians had all their stuff there.

1987

Joanna Gleason As the Baker’s Wife in Into the Woods

“There was just this feeling of us-ness.”

In Into the Woods, Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s complex musical built from classic fairy tales, Gleason’s character and her baker husband are sent on a quest in Act One, to be rewarded with a baby if they succeed. In Act Two, their life (like those of the other characters) proves less than happy ever after.

The Baker’s Wife is just this Upper West Side kind of Jewish lady who marries the Upper West Side guy, and they move to a place because it’s cheap and they start a bakery and the neighborhood turns out to be sketchy. She’s not elegant, but she is thoughtful.

Lar Lubovitch, the great choreographer, came in to choreograph sections. That’s when I figured out how she moves, how pliable and kind of rubbery her spine is, what her stance is. I have to do a lot of traveling — running down across the stage, underneath, coming up. It was very physical to get where I needed to be all the time. I was killed onstage by the Giant — falling back off the stage — which, of course, the arthritis in my neck has been a constant reminder of, but never mind.

One delightful night was when Leonard Bernstein was in the audience. He was in a house seat about five rows back on the aisle. I was singing “Moments in the Woods” and got to a particularly clever lyric, and I heard him go “aaah.” One composer signaling another, one lyricist signaling another: “Nice job.”

Back then, I would go to Orso and there would be Ron Silver from Hurlyburly and Frank Langella and a bunch of other people. We’d all sit at a big round table between shows. There was just this feeling of us-ness.

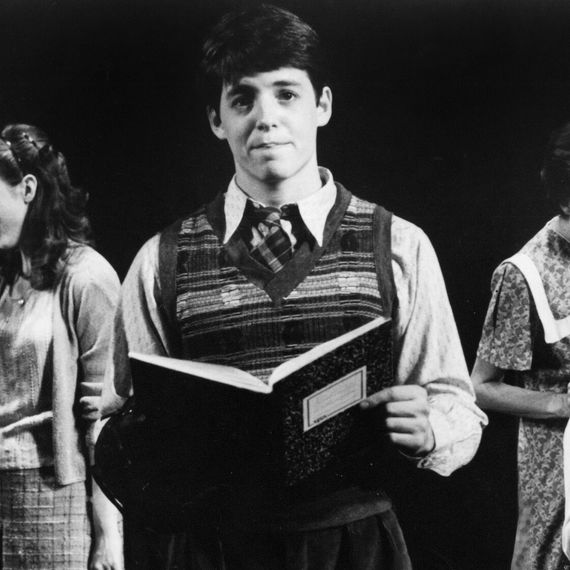

1977 and 1979

Andrea McArdle and Sarah Jessica Parker As Annie in Annie

“Andrea was and remains the queen,” says Parker.

McArdle was 13 when she starred in the title role of Annie. To this day, every kid who plays her, from summer camp to professional productions, still belts “Tomorrow” in her style.

In the tryout in Connecticut, I got cast as the toughest orphan — later named Pepper — and the show was terrible. They were trying everything. We used to have 17 pages of rewrites a day. There’d be characters like Eleanor Roosevelt, and you’d come in the next day and hear she’s dead. Opening night was four and a half hours. The orphanage set fell down and almost killed the conductor.

A few weeks after we opened, Mike Nichols comes and says, “Your show, it’s a hot mess, but I want to produce it for Broadway.” The little girl who had been playing Annie was so beautiful and winsome. And it must have been a week later that Mike Nichols decides that they actually need a kid who’s loud and has street smarts and is thick and funky — and they saw those qualities in the toughest orphan.

Once we got to Broadway, one of the stagehands used to go to this famous bar right next to the Alvin Theatre called Jilly’s between scene changes to have a shot. So one night he comes back and says, “Sinatra is over there.” I go, “What?!” Because for me, everything I learned, I learned from Sinatra. He goes, “Yeah, he’s asking for the kid.” I said, “Who’s the kid?” He said, “You!” I slipped right out the stage door. And all of a sudden the scene is going into “Tomorrow” and they’re like, “Where’s Andrea?” One of the stagehands says, “Uh, she might have gone into Jilly’s to talk to Sinatra.” The stage manager, Janet Beroza, comes in, drags me by the scruff of my neck, and throws me onstage. The orchestra had to hold for — I can’t imagine how long.

Parker joined Annie as July, one of the orphans in the ensemble, and understudied the title role for a year before taking it over.

Andrea McArdle was and remains the queen — not because she behaved like a queen but because she was inarguably the standard-bearer for the role. I went to see it soon after it opened with standing-room tickets, and my father told me, because I loved it so much, “Oh, you’re not really Annie material.” Because I didn’t know I could sing. But I came to the audition and sang “Nothing” from A Chorus Line, and I was cast in the role of July and the second understudy to Annie. On my first night, there was the biggest snowstorm in New York in 30 years, and Andrea’s train was delayed from Philadelphia, where she lived. It was pretty terrifying that I might have to play Annie on my opening night, but Andrea made it. I played an orphan for a year, almost to the day, and Annie for a year, almost to the day.

One night, my second-grade teacher, Joan Ryder, came all the way from Cincinnati to see me. That night, my brother had fixed beef stroganoff at home, and I don’t think it was his fault, but I started vomiting at the top of Act One. The prop guy had pulled in a big garbage can for me to run offstage left and vomit into, and I had run offstage to the point that Mr. Warbucks, Reid Shelton, would say, “Annie will be right back.” By intermission, it was very clear I couldn’t get through it. I was just devastated.

We were regulars at Studio 54, which makes absolutely no sense. We would just walk around, mouths agape. But we were also very normal kids. At a place called Joe G Pizza, with $5 I could get a slice and a drink and I still had about $4 left for the arcade. It had a stand with nuts, candies, Skee-Ball, and pinball. My nickname became Pinball Parker.

2005

Cherry Jones As Sister Aloysius in Doubt

“Five minutes in, you could feel the audience sit up.”

As a nun who suspects that the priest in charge of her school is an abuser, Jones’s character gave as good as she got. Doubt won the Pulitzer Prize.

When I first read Doubt, I was really excited, and I don’t often feel that way. There were several actresses whom they had asked before me, but no matter if you’re the first offer or the fourth — if it’s the right thing, you don’t care. It was 90 minutes long, and five minutes in you could feel the audience sit up. The people who would always agree with Sister Aloysius were young mothers, and the people who would side with the priest were elderly Jews because, to them, I was McCarthy — it was a witch hunt. It was me, the system, persecuting this young man. Everybody who wasn’t a young mother or an elderly Jew was up for grabs. You could tell what the audience, or at least an audible part of the audience, felt in that final showdown. All the writer, John Patrick Shanley, gives poor Sister Aloysius is “I saw you touch William London’s wrist … and I saw him pull away.” I could hear people almost hiss at me.

In 2010, I was doing Mrs. Warren’s Profession with Doug Hughes, also the director of Doubt, and I said, “Doug, I realized I don’t know Flynn’s backstory — will you tell me?” He said, “Of course. What do you think it is?” And I said, “It’s whatever’s the most fun for the actor to play, which would be that he had never touched a child but struggled every single day not to.” And Doug said, “You’re half-right. He hadn’t ever touched a child at St. Nicholas, but he touched every child he could get his hands on in every parish he’d been sent to before.” You could have blown me over with a feather. I felt my pulse drop. I had never thought that. It made me really proud of Sister Aloysius, defending her flock from the wolf.

1996

Idina Menzel As Maureen in Rent

“A lot of us wore our own clothes.”

Jonathan Larson’s Rent, an adaptation of La Bohème set in a decaying and AIDS-ravaged East Village, made a huge splash for two reasons: It felt uncommonly fresh and young, and Larson died suddenly at just 35 after the final dress rehearsal. Menzel is now starring in Redwood, which like Rent is at the Nederlander Theatre.

When I auditioned, I was living with two other girls in one apartment, literally trying to get jobs and pay my rent. I sang “When a Man Loves a Woman” and “Something to Talk About,” by Bonnie Raitt. I was in my “wanting to get a record deal, be a rock star” mode, and I had forgotten from NYU that you mark up your sheet the way you want the accompanist to do it. At the end, there was a coda, which just means repeat, and I had not marked how to complete “Something to Talk About,” so the pianist just kept repeating and repeating and repeating. I didn’t know when we were going to stop. I was trying to end it with a big riff. I was able to show them my spontaneity and my ability to improvise, but I also remember seeming kind of messy for an audition. I came in the patchwork suede skirt that I actually wore in the show. A lot of us wore our own clothes. Now the costumes are made to look like our real clothes.

We had a sense of doing something special, but whether that meant a little Off Broadway run down in the East Village or … I never imagined that it was going to move to Broadway. It seemed very alternative and East 4th Street.

1960

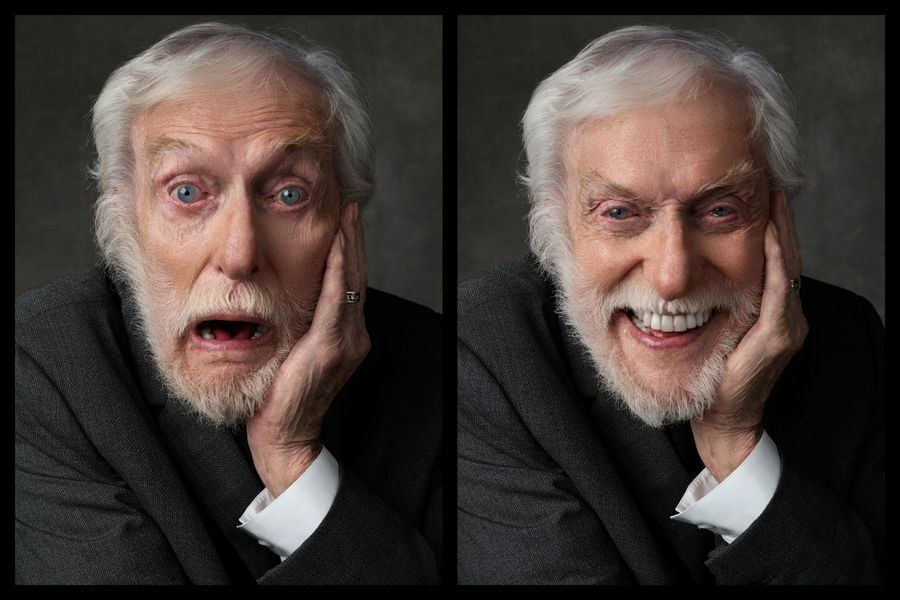

Dick Van Dyke As Albert Peterson in Bye Bye Birdie

"Good God, it was fun!"

The year before his first namesake sitcom premiered, Van Dyke — who turns 100 this December — won a Tony as Bye Bye Birdie’s Albert Peterson, a songwriter left in the lurch when his Elvis-ish rock-and-roll performer is drafted.

I’d always been limber and loose, but I’d never danced before. When I auditioned for Gower Champion, I did “Once in Love With Amy,” the Ray Bolger song, and I did a little soft-shoe, which is all I knew. And he came up and said, “You have the part.” I said, “Sir, I don’t dance.” He said, “I’ll show you.” And he did. I couldn’t stand there and do pirouettes for an hour, but I could certainly get levitation and cross the stage fast. It was like learning to fly. My God, yay. I was all over that stage. Couldn’t stop.

In Philadelphia for the tryouts, I was not a big hit. The show got rave reviews, and at the end, they’d say, “Dick Van Dyke is adequate.” And I thought, I’ve got to go to work, on the dance particularly. Chita Rivera was such a help — she knew more about the stage than anybody, and she taught me so much. Chita had physical prowess like I never saw. I think she could leap higher than Nijinsky — my God, she was a strong girl on top of everything else.

One day, they came down with a new song they’d written for Chita. And bless her heart, she said, “You know, Dick doesn’t have much to do in the first act. Why don’t we let him do it?” It was “Put on a Happy Face.” And that’s what won me the Tony. She just handed me that song.

The finale was just Chita and me dancing, and one night we fell down, both of us. I don’t know what it was — our belt buckles got caught on each other? — and then we jumped up and took a bow and got a big hand. Audiences love to see mistakes. There was a dance number called “One Hundred Ways,” a ballet where the dancers hand me a lily and put a thing on me and I go up. And I just hung there till the number was over. One night, I’m hanging there and, ping, one of the wires breaks and I’m hanging by one wire. I started to turn. I thought, I’m either going to kill myself or a dancer, and it held. When they let me down, I was so dizzy I fell on my face.

Back in those days, the Tony Awards were just a dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria. I was in L.A., where I had started The Dick Van Dyke Show. I didn’t know I had won. They sent me a telegram, which the guy stuck under the welcome mat. It was days before I saw it.

I wore all my own clothes in Birdie. I had my own suits made. One night after the show, a knock on the door and in walks Cary Grant, who pushed me aside and went over and started going through my suits — he liked the way I dressed. Another night, they told me “Fred Astaire is in the front row.” Naturally, I was a wreck. One day, I’m driving to work and he was being interviewed on the radio, and he said, “I like the way Dick Van Dyke moves,” which almost rolled me off the freeway.

My whole life was unplanned. Just the next opportunity that came along — one great thing after another. I never planned anything. One job led into another one, and I just kept working and enjoying it. I’m a ham. I don’t know, something happens and I come alive and I want to perform. I would have starved in any other business. Being on the stage — there’s nothing like it in the world for anyone who can experience it. I pity the people who can’t get on the stage. Good God, it was fun!