It’s no secret that we have an education problem in America. The U.S. ranks 18th in the world for education based on PISA scores, yet it ranks fifth in amount spent per pupil.

The U.S. has made attempts to try and reverse course on this issue, such as the establishment of the Department of Education in 1979, and the introduction of the Common Core curriculum in 2010, although these have not helped the situation get any better.

Given these unsuccessful endeavors, it seems only right to look at countries that are well known for their strong educational systems. East Asian countries, for example, are renowned for their high academic achievement, which produces an extremely skilled workforce.

China, Japan, and South Korea rank second, third, and fifth in global academic ranking, respectively. In terms of spending per pupil, South Korea ranks fourth, Japan 20th, and China last.

Let’s take South Korea as an example.

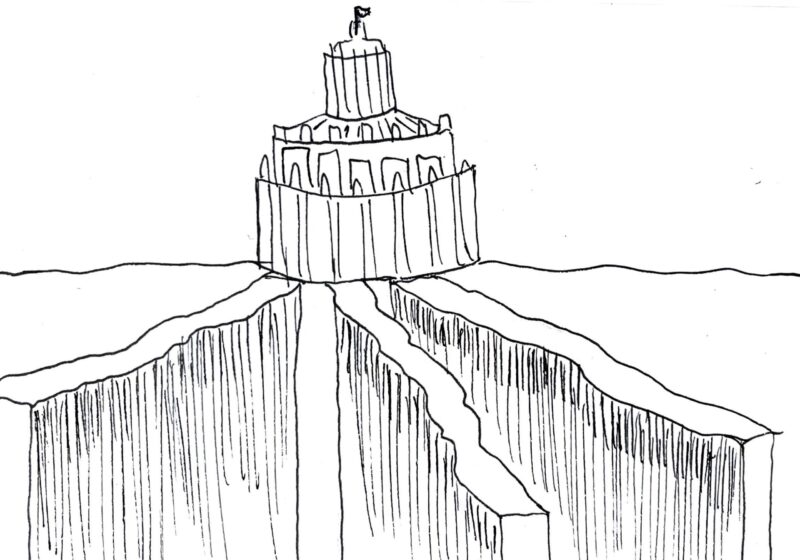

After the Korean War ended in the 1950s, South Korea greatly expanded secondary and technical education for the growing labor force fueling the country’s export-driven economy. Because of the new opportunities being opened up by education, families began to invest heavily in the education of their children. This led to the rise of the hagwon, a type of cram school. With an increasing number of children attending these cram schools and scoring higher on the Sueneung, Korea’s primary university entrance exam , competition for higher education became even more fierce.

Entry into South Korea’s prestigious SKY (essentially the Ivy League of South Korea) universities — Seoul National University, Korea University, and Yonsei University — is seen as a crucial step on the path to a successful career. The main driver of this attitude are the country’s “chaebols”, the largest companies in the country, which offer competitive salaries and benefits compared to smaller companies. Of course, these chaebols almost exclusively hire SKY university graduates.

The situation in China and Japan isn’t much different.

In China, the Gaokao exam is effectively the sole factor in determining university admission, with prestigious institutions like Peking University and Tsinghua University creating pathways for high salary jobs. Cram schools also are present in China, with some of the schools’ students facing 16-hour days.

In Japan, the “Kyōtsū Tesuto” or “Common Test” is a crucial factor in determining one’s university choices. Careers in the Japanese government or corporations listed on the Nikkei 225 (sort of like the Japanese version of the Fortune 500, including notable Japanese companies like Toyota and Sony), typically favor graduates from prestigious universities, such as the University of Tokyo. However, Japanese students typically study less during out-of-school hours when compared to their Chinese and South Korean counterparts.

Beyond occupational benefits, what seems to drive this emphasis on education in East Asian countries is the cultural emphasis on hard work and meritocracy, which are values derived from a deeply rooted history of Confucian values.

However, this academic success comes with many consequences.

Among Chinese students, 54% say that they experience depression or anxiety due to the pressure of school admissions, 43% because of parental expectations, and 40% due to exams. In South Korea, suicide is the most prevalent cause of death among adolescents, affecting seven in 100,000. Academic stress contributes to 12% of adolescent suicides nationwide.Academic pressures have also been linked to an increasing rate of bullying and suicide among adolescents in Japan as well, often associated with the pressure placed on students from their parents, teachers, and peers.

The consequences of overworking are too great to overlook, and are likely what will stop the U.S. from ever following in the footsteps of these countries. Evidently, academic reform in efforts to maximize success is incredibly difficult to implement, especially in a way beneficial to both student success and wellbeing. If the U.S. wants to change course regarding its declining academic performance, this will require a sensitive balance between academic reform and changes to our national values.